Our first visit to Pembrokeshire was over a wild, wet and windy weekend in November 1970. This should have been enough to deter us from subsequent visits, but there was something about the landscape, the air and the surrounding seas that captured our imagination. Since then we have returned many times, both by ourselves and later with our children. This land of enchantment, the Gwlad yr Hud of the Mabinogion, has been a source of magic and mystery since before the bluestones of Prescelly were taken from these sacred hills and re-erected on Salisbury Plain, in an early phase of Stonehenge development.

As well as its lonely and mysterious central mountains, Pembrokeshire has probably the finest cliff scenery in southern Britain, a number of dramatic Norman castles, fine churches and lovely river valleys. But it was to the remains of an earlier age that we first turned our attention. I refer to the numerous Neolithic tombs, or cromlechs, the magnificent iron age hill forts and cliff castles and the bronze age standing stones on lonely highways.

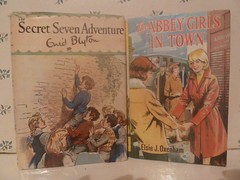

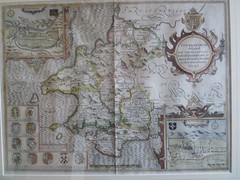

It was not long before visits to the Reference Section of Haverfordwest Public Library had fired our enthusiasm for searching out books on Pembrokeshire, its antiquities and its history. However it was on a visit to Chester that we acquired the first volumes in what was to become our Pembrokeshire collection - the first two volumes of George Owen's 'Description of Penbrokshire', published by the Cymroddorion Society. George Owen's description was first published in 1603 and contains a famous drawing of the magnificent chambered tomb of Pentre Ifan.

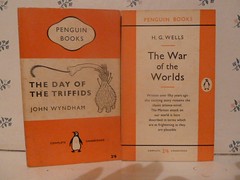

It was in these books that we found a reference to Richard Fenton's 'Historical Tour Through Pembrokeshire', so this became our next quest. Here I must introduce the first of three great booksellers of the old school, all of whom are sadly no longer with us. This is Stanley Crowe, whose shop in Bloomsbury Street became a Mecca for us on our visits to London. The rather cramped shop at street level was but the portal to the steep and narrow stairs that led to the extensive basement, filled with bulging shelves stacked with topographical works. Strategically placed buckets caught any water dripping from the ceiling. There was an inner sanctum in the basement for the really fine books, but this area was not for browsers. There were enough treasures in the rest of the basement, including a Welsh section. Sure enough, Stanley Crowe could offer two copies of Fenton, the 1810 first edition in half calf, or the buckram bound later second edition, at a quarter the price. We did what any true collector would, swallowed hard and committed a week's salary to the former.

Over subsequent visits we got to know Stanley Crowe and his assistant, Mary Booth, later Mary Hubbard, well. They helped us to add to the Pembrokeshire collection and to branch out into the neighbouring counties via such works as J E Lloyd's 'History of Carmarthenshire', Jones's 'Brecknock' and Meyrick's 'Cardiganshire'.

The second in my triumvirate is Tom Lloyd-Roberts, where over morning coffee, served by his mother in the elegant lounge of the Old Court House at Caerwys, near Mold, he would talk eloquently of all things Welsh, and in particular his greatest interest, Thomas Pennant, who embarked on his series of tours in the late 18th century from his home at Downing nearby. It was on one of these mornings that we added to our collection Edward Laws' 'History of Little England Beyond Wales' and Colt Hoare's magisterial translation of 'The Itinerary of Archbishop Baldwin Through Wales' by Giraldus de Barri, Gerald the Welshman, whose home was the lovely castle of Manorbier on the South Pembrokeshire coast.

And finally, to Hay-on-Wye, the world's first book town, which in the early 1970's, under the leadership of Richard Booth, was, in my opinion, at its peak. Here, in the old Fire Station, we got to know Major Egginton, a distinguished gentleman, very much of the old school, who oversaw the topographical section of Richard Booth's bookshops. Here were treasures galore - county histories, tours and maps - and here we could add Lewis's "Topographical Dictionary of England and Wales", with the attractive county maps to the collection. We could also spend time handling books we could not afford and browse in the upstairs of the shop where treasures could be found in seemingly random stacks on tables and on the floor. I particularly remember a pile of copies of "Cardigan Priory in Olden Days", by Emily M Pritchard. Also a number of copies of George Owen's "The Taylor's Cussion", a collection of his miscellaneous jottings on Pembrokeshire and South Wales. It was this seemingly haphazard abundance that gave to Major Egginton's empire its magical quality. Find me a provincial bookshop now with such depth to it's holdings!

As time has passed, we have explored other counties and countries, rarely without seeking out the key books which encapsulate the spirit of the place; but the excitement of our early ventures as we attempted to form a Pembrokeshire collection remains an essential first step of our book collecting journey.

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPad