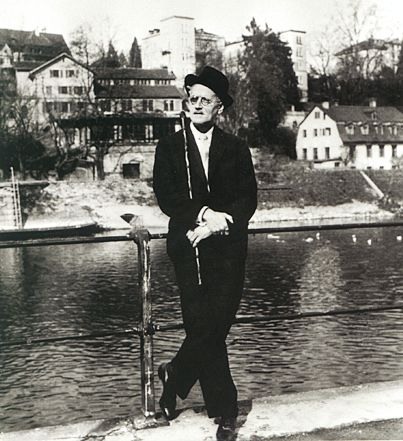

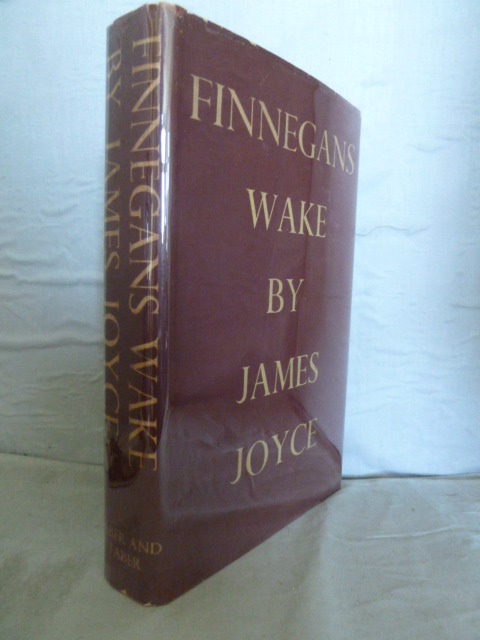

It is a truth universally acknowledged that, for all except a select band of devotees, in 'Finnegans Wake' James Joyce bequeathed as his parting gift to the world a book that is essentially unreadable. Yet any list of the world's great books would include Joyce's 'book of the dark' alongside his book of the day, "Ulysses". To its admirers it is the greatest book of the twentieth century; to others it remains a mystery as yet unexplored.

It is complex, deliberately made so, as Joyce expanded and revised earlier drafts, creating ever richer neologisms and portmanteau words and incorporating words from a variety of languages. It is the multiplicity of meanings and interpretations contained in each phrase (and often word) that makes 'Finnegans Wake' the magical work it is. This, in turn, has led to a veritable industry of commentators, annotators and critics who have subjected the book to possibly the most detailed examination ever accorded to a modern work of fiction.

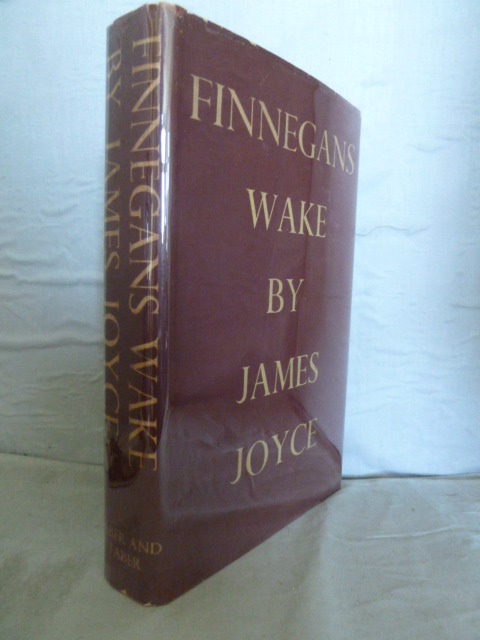

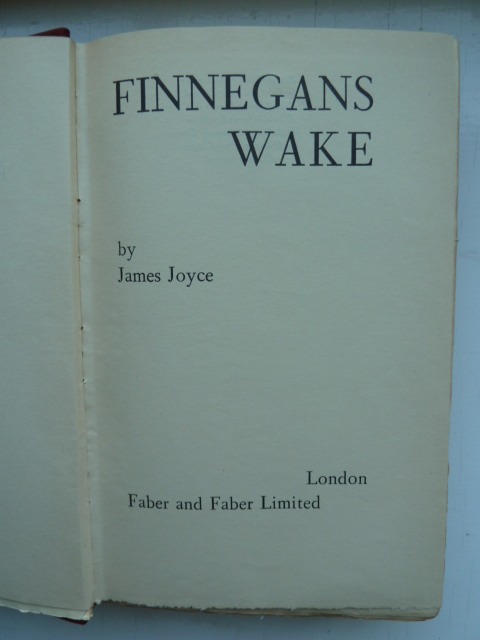

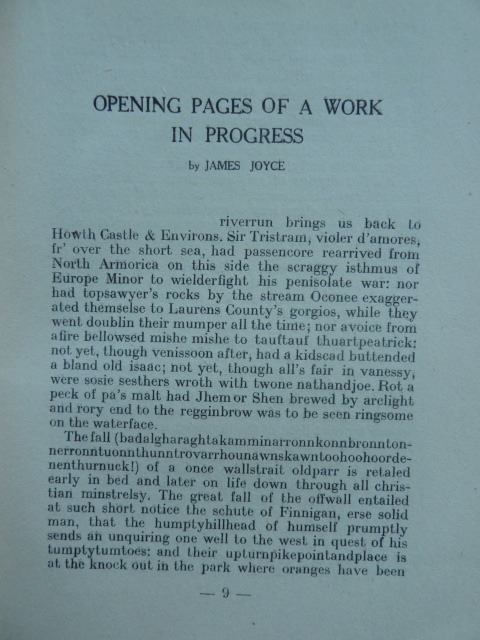

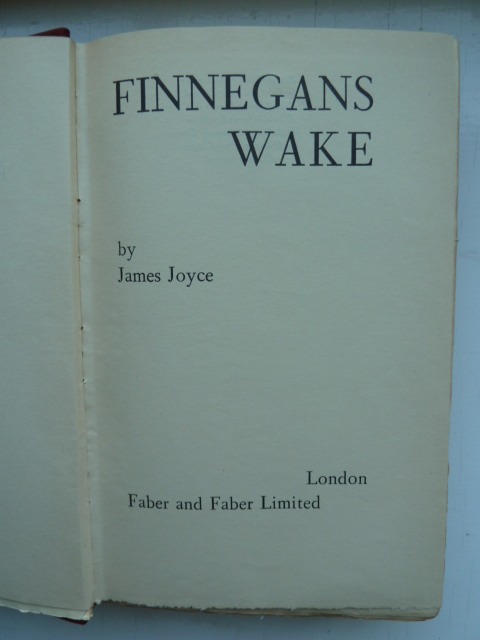

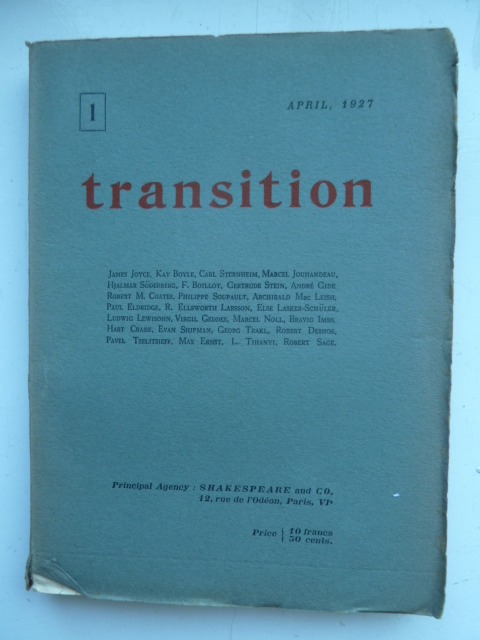

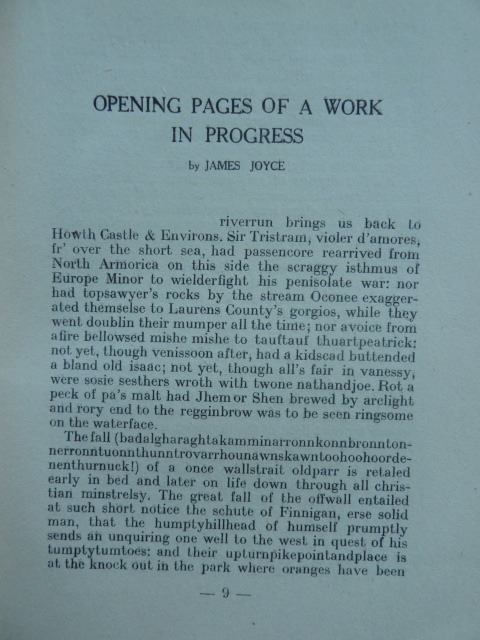

This process began even before the book was published in its final form by Faber and Faber in 1939, as a result of the publication in the journal 'Transition' of extracts from what was then called 'Work in Progress'.

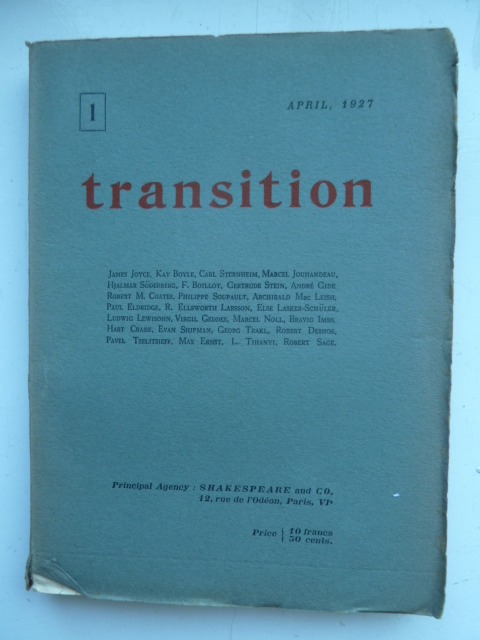

These extracts in fact comprise the bulk of the work and were published in 17 installments between April 1927 and May 1938, Joyce having commenced his 'Work in Progress' in 1923, the year after 'Ulysses' was published. 'Transition', published by Sylvia Beach's Shakespeare and Company contained alongside 'Work in Progress', work by other leading modernists, such as Gertrude Stein, Marcel Duchamp, Kurt Schwitters and even Franz Kafka.

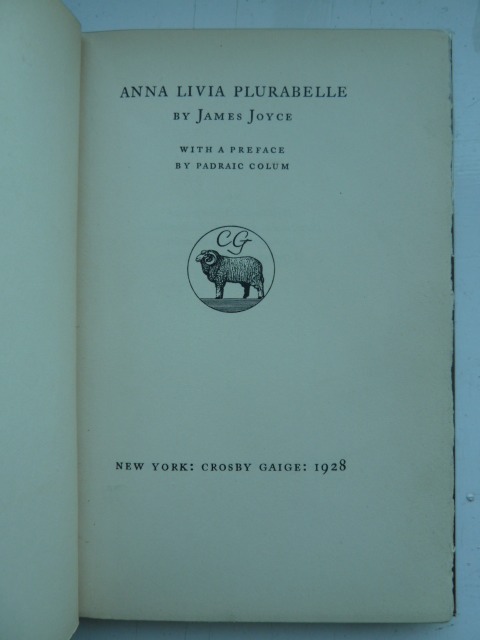

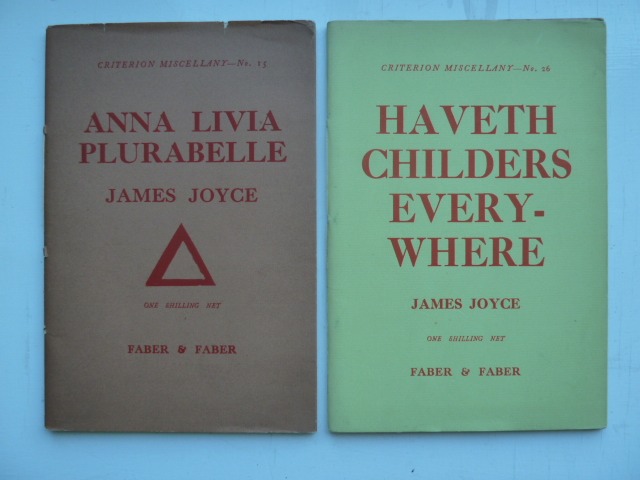

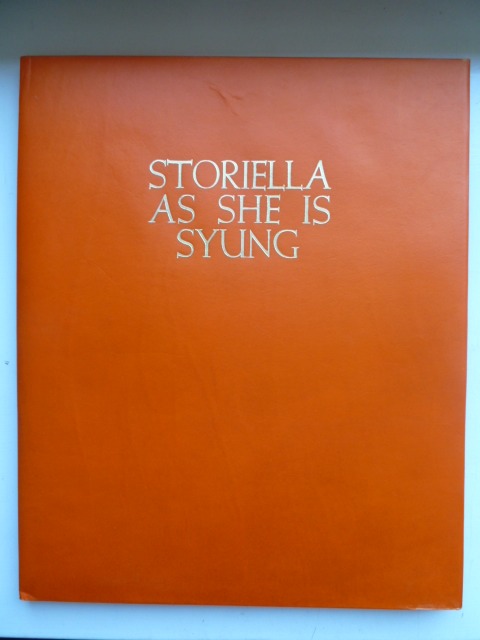

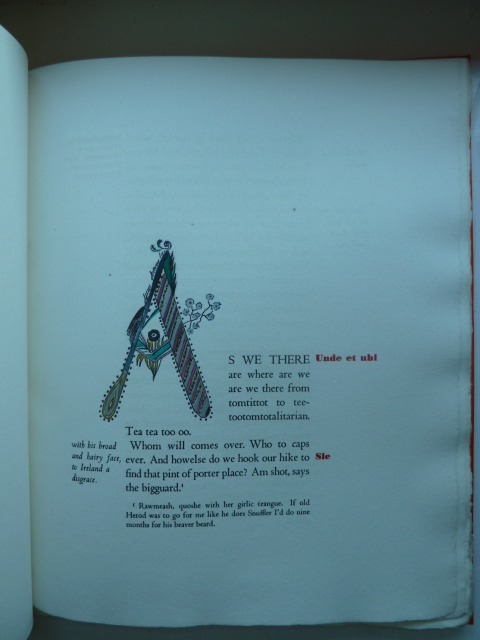

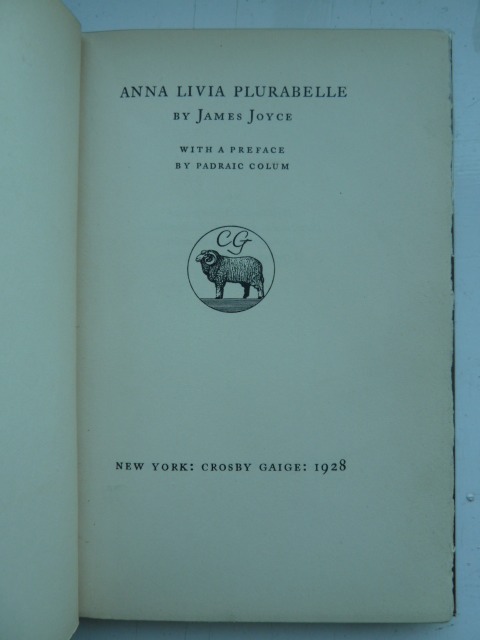

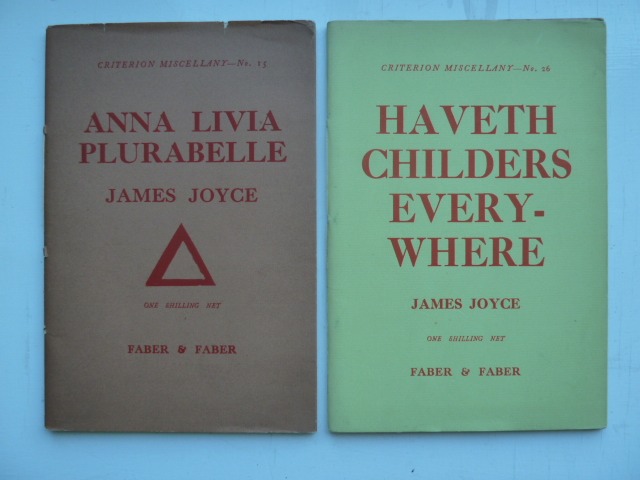

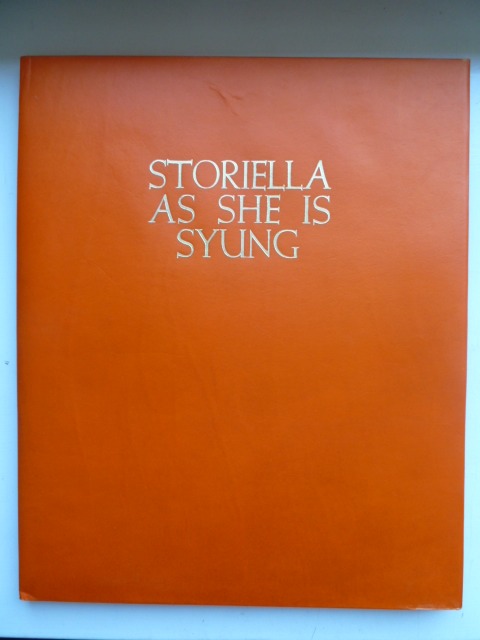

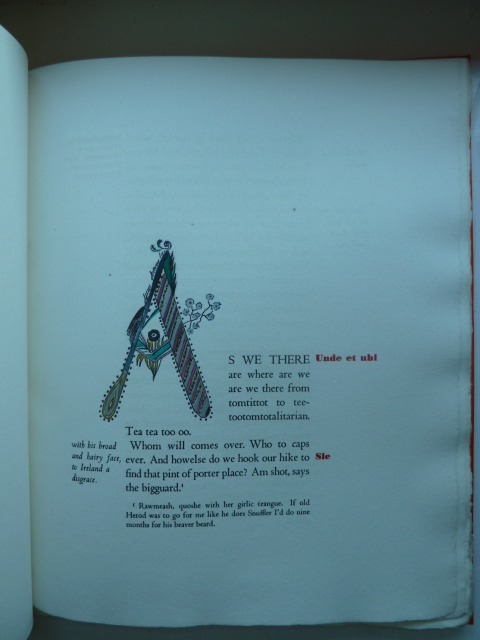

Sections of the work were also published in individual booklets by private presses, such as the Paris based Black Sun Press and the New York Crosby Gaige. Copies of these, especially the signed ones, can be very expensive. The first of these was 'Anna Livia Plurabelle' (1928), the last (and most elaborate, including a hand coloured initial letter by Joyce's daughter, Lucia) 'Storiella as She is Syung' (1938).

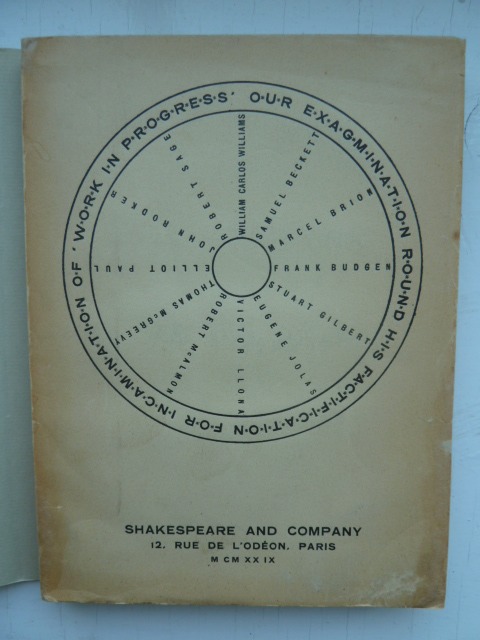

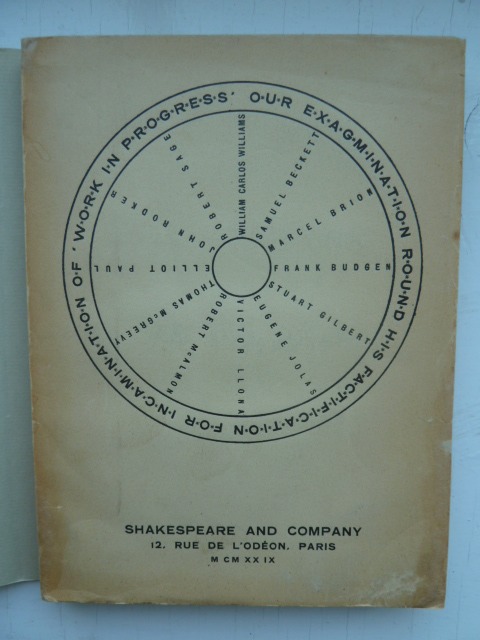

Only two years after the first appearance of 'Work in Progress' in 'Transition' Joyce encouraged a group of friends to publish their responses to it. Thus it was that in 1929, Shakespeare and Company published 'Our Exagmination Round his Factification for Incamination of Work in Progress', containing articles by, amongst others, Samuel Beckett (to whom Joyce dictated parts of 'Work in Progress' as his eyesight failed) and William Carlos Williams, surely the only occasion on which a spirited defence of a book has been published ten years before the actual book was published. A significant number of Joyce's letters to his friends also contain explanations of various parts of his text.

But then everything about 'Finnegans Wake' defies the usual conventions; it is one of those works like 'Tristram Shandy' and 'Alice's Adventures in Wonderland' that changes the landscape of literature. For a start, since its original publication, successive editions have maintained essentially the same pagination, from Page 3 through to 628, enabling references in critical works to page and line numbers to have universal application. This is similar to the Bible, with its generic Book, Chapter, Verse references and, in my mind, 'Finnegans Wake' is Joyce's sacred book, since into it he poured not only his own life experience, but a view of life that is both universally valid and profoundly sympathetic. Joyce's writing style, in this work, has all the characteristics of a dream, with characters undergoing transformations both to heroic archetypes and to geographical features. But the identity of the dreamer is not certain.

Who are the characters? Essentially a family living in a public house in Chapelizod, on the banks of the Liffey west of the centre of Dublin, at which house, a party has assembled for the wake of one Finnegan, a builder who fell from a ladder. The family are the publican, Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker (HCE), his wife Anna Livia Plurabelle, their twin sons Shem and Shaun and daughter Issy. But these characters represent all of humanity.

HCE is the archetypal flawed man, who has committed some sort of indiscretion in Phoenix Park, from which event much of the book's narrative action (such as it is) is derived. But he is also the mythical hero of his race, Finn MacCool, and a builder of cities and civilisations. His geographical counterpart is Howth Head, where the Liffey meets the Atlantic.

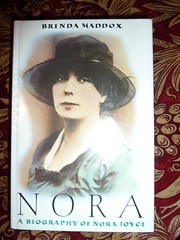

Anna Livia is all women and has her counterpart in the 'rivering waters of, hitherandthithering waters of' the River Liffey, Dublin's passage to the sea. She is a subject of gossip amongst the washerwomen down at the river but is the well spring of all life.

Shem 'the Penman' is the writer and artist (possibly Joyce), Shaun 'the Post' is the practical son (possibly Joyce's brother Stanislaus), deliverer of messages, while the lively Issy is every daughter.

Through these characters in their multiple avatars Joyce presents a view of all history, geography and literature. Finnegan's fall is Earwicker's fall is humanity's fall. Joyce was Influenced by the Italian philosopher Vico's theory of history as repeating cycles (successive ages of gods, heroes and humans followed by a period of chaos before the cycle repeats) and this cyclical pattern occurs thoughout the book, evidenced also by the first sentence of the book being the continuation of its final sentence.

I (perhaps like many others) read selected parts of 'Finnegans Wake' before attempting the whole book (which I have now done). To help I assembled a collection of, what have become standard 'companions' to the 'Wake'. Perhaps the best known of these is 'A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake' by Campbell and Robinson (1944), which contains analysis and a paraphrase of its text.

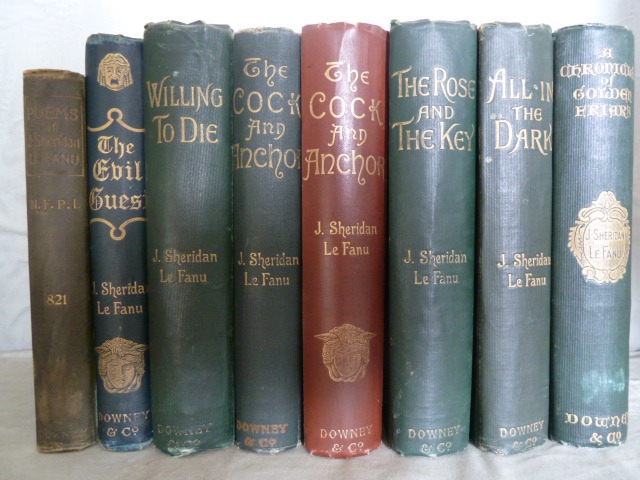

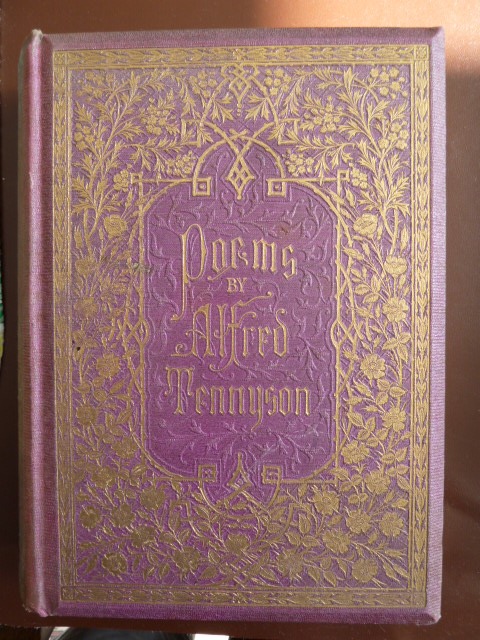

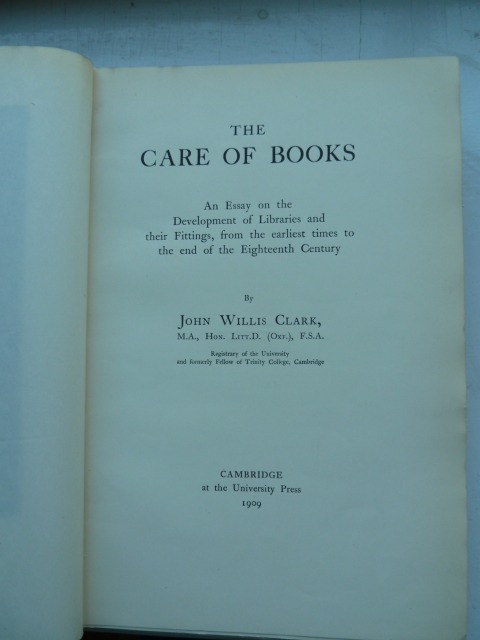

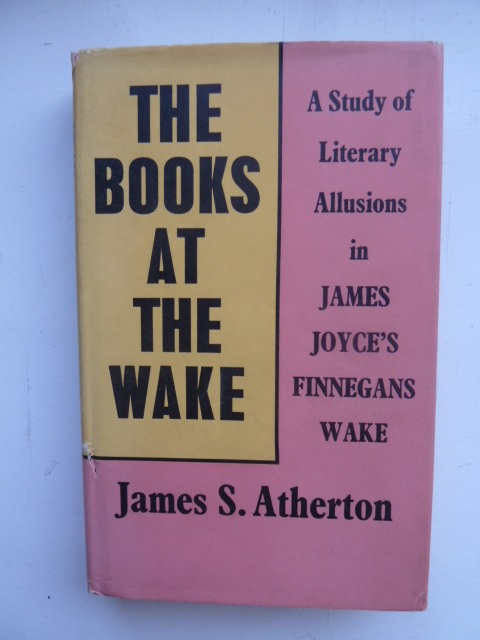

My own favourite is James Atherton's 'The Books at the Wake' (1959), which is a detailed study of the literary sources Joyce used. These include Skakespeare (every play is incorporated), Swift, Lewis Carroll, The Bible (every book) and the Koran (all 114 suras). But Joyce also built in references to his favourite books, such as Le Fanu's 'The House by the Churchyard' and Thomas Moore's 'Irish Melodies' (all first lines and titles of the melodies are used). Atherton lists several hundred separate works which can be found in the 'Wake', including the 11th edition of the 'Encyclopedia Brittanica', which Joyce plundered for river names and other geographical and historical references.

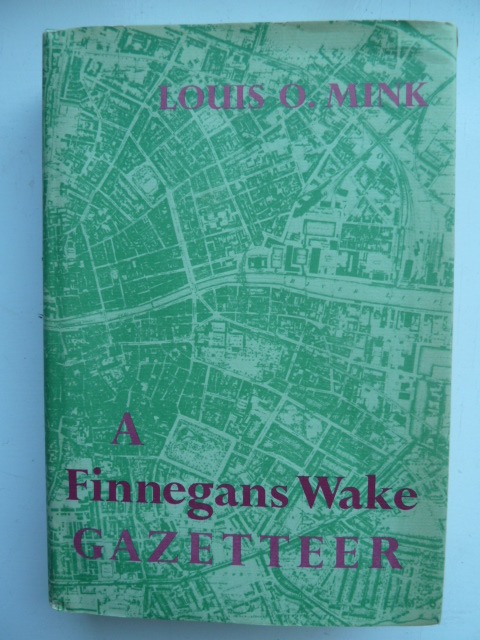

Louis Mink's 'A Finnegans Wake Gazetteer' (1978) includes references to the thousands of place name references, arranged both in linear form (i.e. in order of the text) and alphabetically.

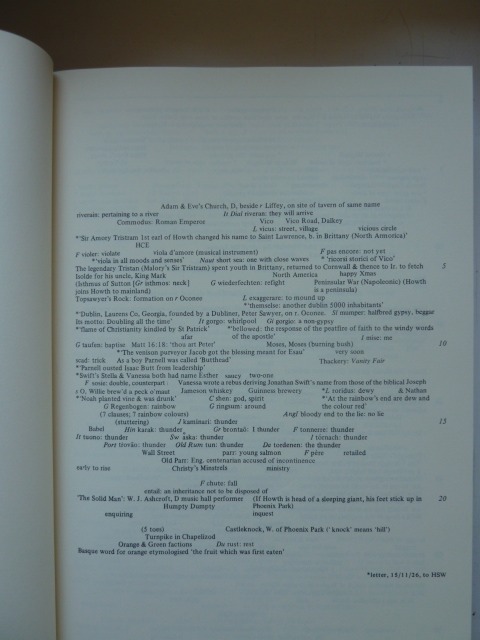

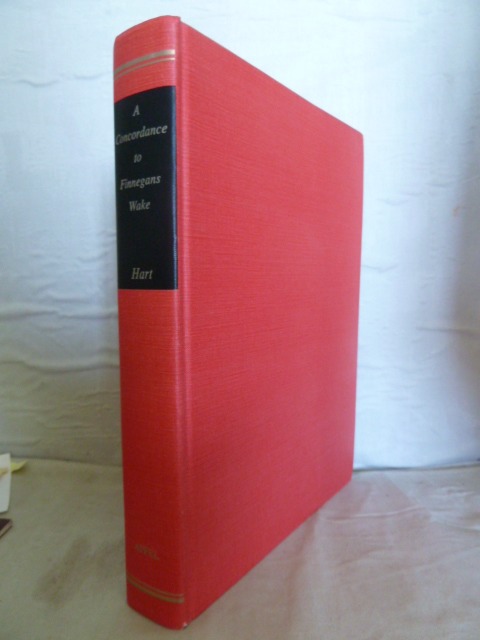

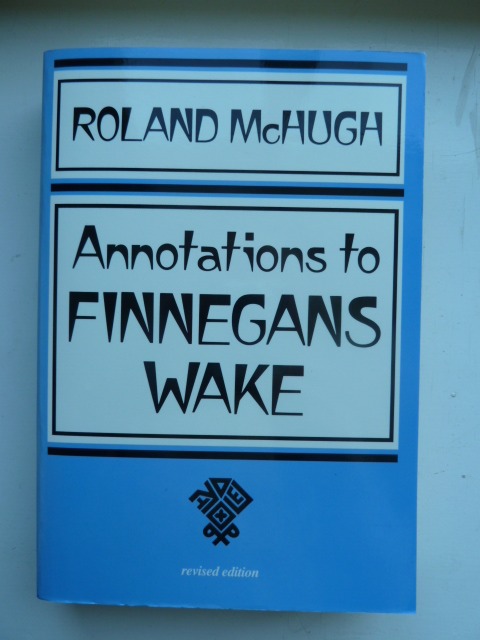

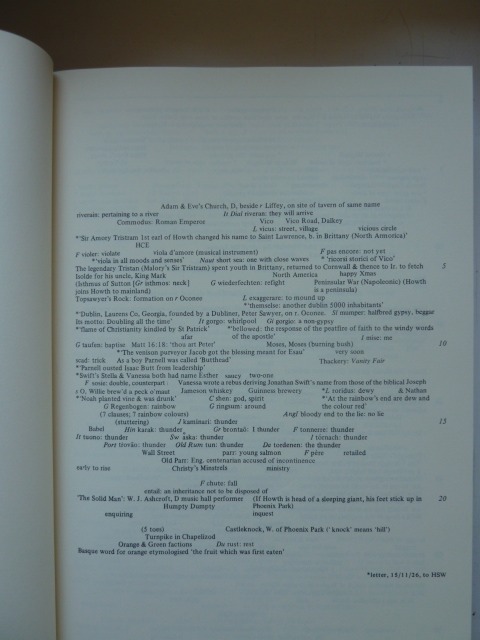

Add to these Clive Hart's massive 'Concordance' and McHugh's 'Annotations', which provides page by page analysis of every word requiring it, and you would be as well equipped as any previous reader.

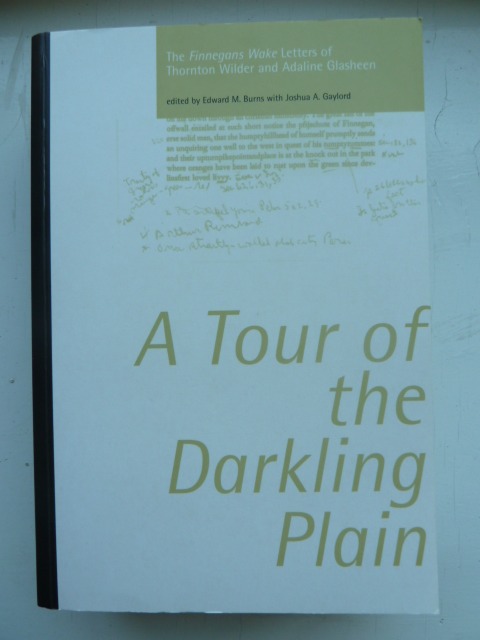

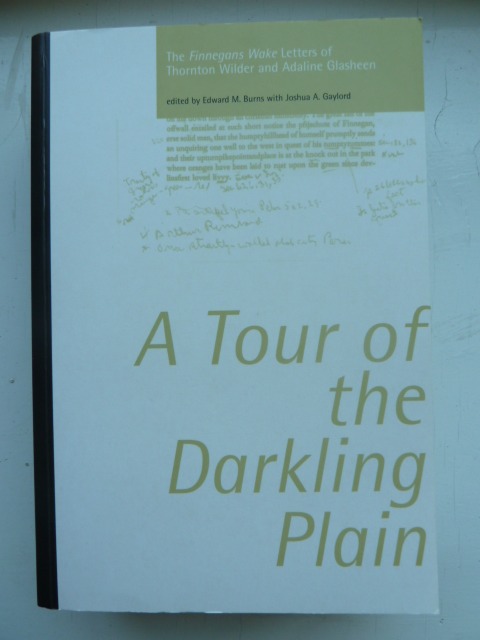

There is a wonderful book edited by Burns and Gaylord entitled 'A Tour of the Darkling Plain'.

This contains letters exchanged between Thornton Wilder and Adaline Glasheen over the period 1950 to 1975, in which they share their love of 'Finnegans Wake' and attempt to solve its mysteries. Glasheen went on to produce the wonderful 'A Census of Finnegans Wake' (1956), which lists the hundreds of characters, fictional and historical, who appear in the work, with suitable annotations. She later expanded this in second and third editions.

So, when to read 'Finnegans Wake'? Perhaps, as Joyce wrote it at the end of his writing life, it is best read late in your own reading life. It is the work of a mature mind at the very height of its powers.

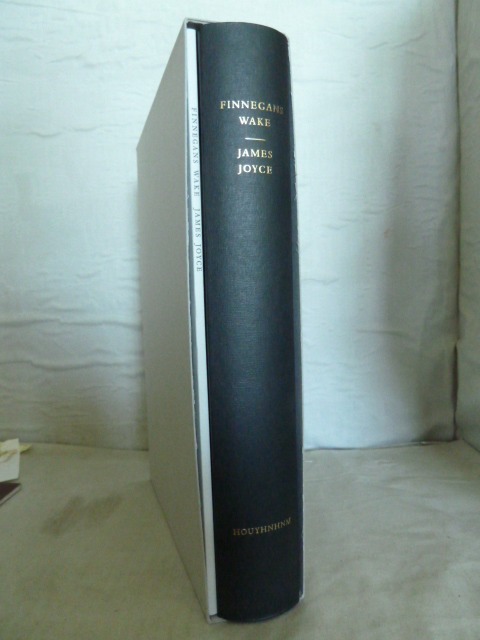

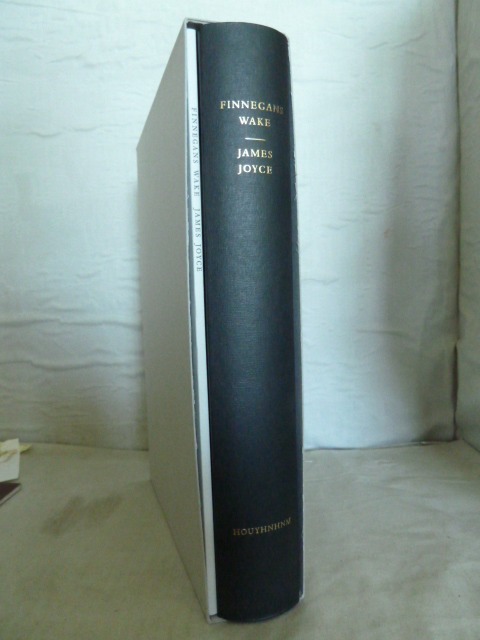

And perhaps now is exactly the right time, as a New Edition of 'Finnegans Wake', the product of many years work on the manuscripts, has just been published in a sumptuous edition by the Houyhnhnm Press, Dublin. This has some 9,000 'corrections' from the previously published version and is perhaps the last word on the text. It will be available in Penguin shortly.

Why read it? Because hidden away you will find (as on page 328, line 29), lines that take your breath away:

"In the buginning is the woid, in the muddle is the sounddance and thereinofter you're in the unbewised again, vund vulsyvolsy.".

For a succint statement of life (and death) that is about as good as literature can get.

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPad