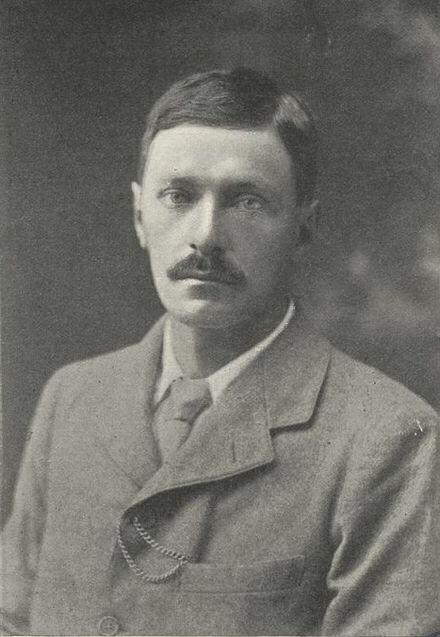

The dinner table has been cleared, the servants dismissed for the night and the remnants of the party assembled for a few days shooting (or fishing) gather round the dying embers of the fire for a last cigar and perhaps one more whisky. The wind will almost certainly be rattling the shutters and the trees tapping on the window. Inevitably, the conversation turns to ghost stories and again inevitably, at least one of the party will have a story to tell. The ladies having long retired to bed, no detail, however horrific, need be omitted - standard preamble to many a fictional ghost story and a setting instantly familiar to many of the protagonists in the ghost stories of E F Benson and, of course, to their author.

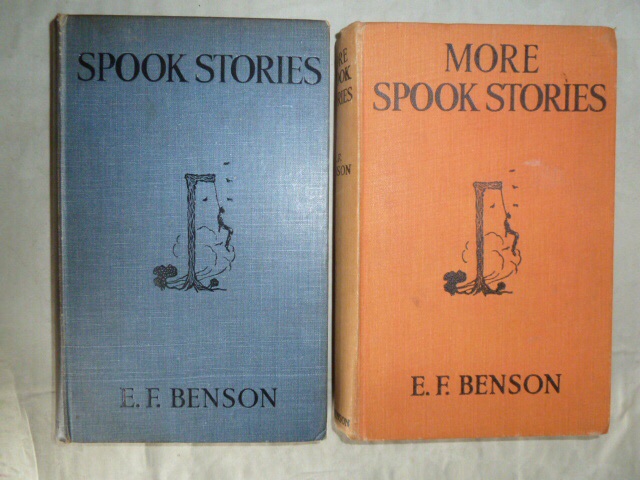

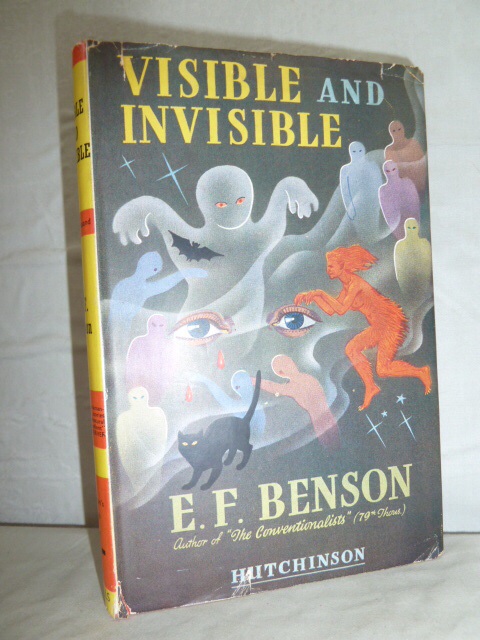

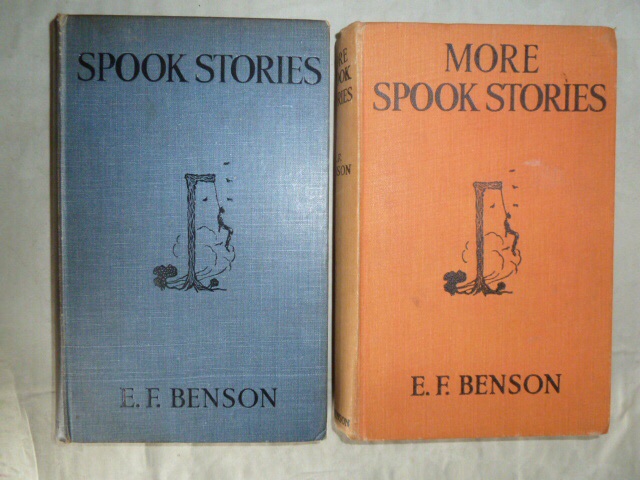

In Benson’s lifetime four volumes of his ghost stories were published, the earliest 'The Room in the Tower' in 1912, the last 'More Spook Stories' in 1934. Benson’s stories followed a particularly brilliant era for the traditional English ghost story, an era that may be said to commence with Henry James’ ‘The Turn of the Screw’ in 1898 and which encompassed some of the best writing in this tradition notably, M R James’ 'Ghost Stories of an Antiquary' 1904), Algernon Blackwood’s 'The Empty House' (1906), and Oliver Onions’ 'Widdershins' (1911).

It is perhaps in comparison with his great contemporaries that Benson’s reputation as a writer of ghost stories may fall below the highest standards. Thus, whilst M R James is the undisputed master of the antiquarian ghost story, Algernon Blackwood of the atmospheric ghost story and Walter de la Mare of the psychological ghost story, E F Benson’s stories do not appropriate for their author any particular sub-category of the genre. However his stories have continued to be plundered by anthologists for the last seventy years or so although it took until 1992 for his collected ghost stories to appear in a single volume.

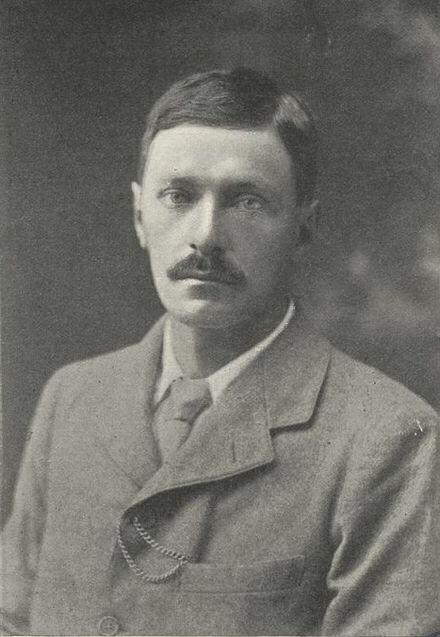

Famously, E F Benson, as a member of the Chitchat Society at Cambridge, was one of the small group who heard M R James make his first ghost story reading in October 1893, when MRJ read two stories, including the much reprinted ‘Lost Hearts’. M R James would go on to produce four collections of ghost stories in his lifetime, as would Benson. They would remain friends for the rest of their lives.

Uniquely amongst his four volumes of ghost stories, 'The Room in the Tower' contains a short preface. Here the author summarises his reasons for writing them:

"These stories have been written in the hopes of giving some pleasant qualms to their reader, so that, if by chance, anyone may be occupying in their perusal a leisure half-hour before he goes to bed when the night and the house are still, he may perhaps cast an occasional glance into the corners and dark places of the room where he sits, to make sure that nothing unusual lurks in the shadow. For this is the avowed object of ghost-stories and such tales as deal with the dim unseen forces which occasionally and perturbingly make themselves manifest. The author therefore fervently wishes his readers a few uncomfortable moments."

This passage is extremely useful in understanding Benson’s intent and explains much about the stories themselves. Each story is relatively short, between 7 and 18 pages long in the collected edition, obviously intended for reading in a single sitting. Such a length precludes the detailed character development found, for example, in Henry James and Walter de la Mare or the extended landscape descriptions found in writers such as Algernon Blackwood and Arthur Machen. However, the strictures Benson placed on himself ensure a concise and rounded story with little distraction from the main effect. It may also be noted that many of the stories were first published in popular magazines such as Pearsons and Hutchinsons, the stories sometimes being illustrated, notably by Edmund Blampeid. Unfortunately, when the stories appeared in book form said illustrations were not included.

Clearly for a magazine appearance short stories had to be written to the length allowed by the editor. This is not to say that Benson was incapable of writing on ghosts and the supernatural in longer works and several of his novels, for example 'The Luck of the Vails' and 'David Blaize', have occult or supernatural content. However, these are outside the scope of this article, except for the light this aspect of Benson’s novel writing throws on his short ghost stories. Clearly, both were evidence of an interest in occult and supernatural forces that was shared by many of his contemporaries, notably Arthur Conan Doyle, another prolific author of supernatural stories. Benson was clearly aware of the fraudulent practices of some supposed clairvoyants, as revealed in stories such as ‘Mr Tilly’s Séance’ and ‘The Psychical Mallards’. In the former, Mr Tilly is killed in an accident while on his way to a séance. In his new spirit form he decides to attend the séance, where he reveals himself to the medium, discovering that she is a fraud. However, he astonishes the group by speaking through her. So amazing is the experience that the Psychical Research Society send independent investigators to check the facts and they conclude that the whole thing was fake, which as the narrator concludes “was a pity, since, for once, the phenomena were absolutely genuine”. This is perhaps the most humorous of the stories and is written with a light touch, with none of the atmosphere of impending catastrophe usually prevalent in the stories.

Famously, E F Benson reported seeing the ghost of a man in the garden of his home at Lamb House, Rye, the Vicar of Rye also being present on this occasion and corroborating the sighting. For a house formerly occupied by Henry James, Lamb House was clearly maintaining a ghostly tradition. In her short novel 'The Haunting of Lamb House' Joan Aiken presents three separate hauntings involving first Toby Lamb, the original owner, then Henry James and finally E F Benson.

It is perhaps something of an irony that ghost stories and reports of ‘real’ encounters with ghosts retained their popularity in an age when science was busily unlocking the secrets of life, the record of the rocks and the structure of matter itself. Perhaps they reflected a belief that there were questions of human experience and perception to which science alone could not provide the answers; or perhaps imaginary horrors provided some measure of escape from the all too real horrors of mechanized twentieth century warfare.

Benson, following his exposure to the readings of M R James and his own experience at Lamb House, had clearly thought about how best to write ghost stories. In his autobiography 'Final Edition' he noted that “by a selection of disturbing details it is not very difficult to induce in the reader an uneasy frame of mind which, carefully worked up, paves the way for terror”. He further suggested “that the narrator must succeed in frightening himself before he can hope to frighten his readers.” Clearly we should not be seeking comfortable, benign, ghosts in his stories, but rather those of a malevolent and threatening kind, very much in the M R James tradition.

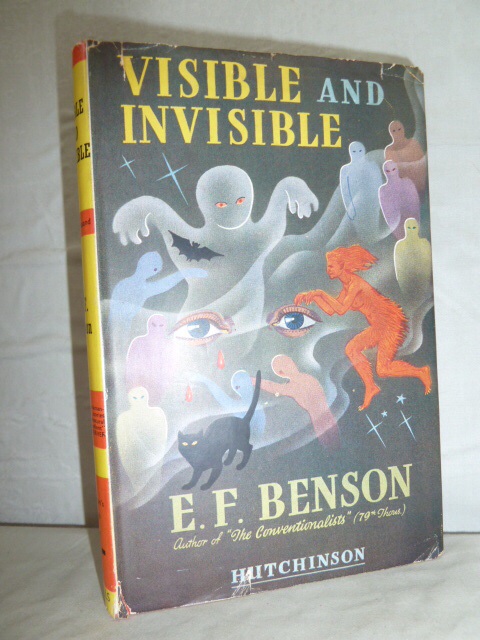

I first encountered E F Benson at the age of eleven when I found two of his stories in the excellent Hutchinson anthology 'Fifty Years of Ghost Stories'. One of these, ‘Pirates’ made a deep and lasting impression. It is one of his finest tales and was included in 'More Spook Stories'.

In ‘Pirates’ Peter Graham, a successful middle-aged business man, returns on business to the Cornwall of his childhood and is haunted by memories of the idyllic time he spent there with his family, now all deceased. Finding his former home available, albeit sadly run down, he obtains the keys, and visits it, all the time encountering signs of his past life there; in particular he remembers the game of Pirates that they played in the garden. He buys the house, has it renovated and finally comes to take occupation. Waking from a dream, he hears his sister calling for him to join them in the garden and his mother’s voice - “They’re all out in the garden, and they’ve been calling you ….” Peter runs out to join them, knowing they will be playing the favourite game of Pirates.

"He scudded past the golden maple and the bay tree, and there they all were in the summer-house which was home. And he took a flying leap up the steps and was among them.

It was there that Calloway found him next morning. He must indeed have run up the winding path like a boy, for the new-laid gravel was spurned at long intervals by the toe-prints of his shoes."

His weak heart had finally failed. ‘Pirates’ is a magnificent story and unlike any other ghost story Benson wrote. It has been called his most autobiographical. Peter Graham is, perhaps, only a thinly disguised version of the author, who, in this story, may be returning to memories of his childhood in Cornwall when his father was Bishop of Truro. The story is full of the nostalgia for childhood and well-loved places of times gone by and Peter Graham is perhaps unique among Benson’s haunted heroes in finding in death a welcome release, rather than a terrifying nightmare.

Moving forward a couple of years I encountered another anthology, Faber and Faber’s 'Best Ghost Stories', selected by Ann Ridler, including Benson’s ‘The Face’. In my opinion this story, included in 'Spook Stories', is Benson’s most terrifying and ranks with the best of M R James. Hester Ward has a recurring nightmare, in which she is walking along a cliff which slopes steeply down to the sea. She comes to the tower of a ruined church, standing in a graveyard. She then sees a hideously distorted face, which, leering at her, says “I shall soon come for you now”. The nightmare has progressed since her childhood and the cliffs been eroded closer to the church tower. In her childhood she recalls the face saying “I shall come for you when you are older”. Sent away to the seaside to restore her nerves, she takes a walk along the cliffs one day and encounters the landscape of her nightmare. She rushes home, telegraphs for her husband to come and awaits his arrival in her hotel room. When the page-boy informs her that a man is waiting for her at the hotel door she rushes downstairs to meet her husband. However, when the visitor turns his face towards her “the nightmare was on her; she could neither run nor scream, and supporting her dragging steps, he went forth with her into the night”. When her husband arrives shortly after a search is made but Hester is never found.

There are, of course, further elements to this story, which make it a true classic of the genre. However, it is not typical of its author. Rarely does a female take centre stage in Benson’s ghost stories and unusually there is no reason for the haunting of Hester. She apparently has done nothing to deserve her ghastly fate. In my opinion, however, the apparent randomness of the choice of victim is a strength of the story. This could, perhaps, happen to anyone.

Both ‘Pirates’ and ‘The Face’ have been widely praised by critics. Indeed in his wonderful essay Supernatural Horror in Literature, H P Lovecraft describes ‘The Face’ as “lethally potent in its relentless aura of doom”. Other stories singled out by Lovecraft are ‘The Man Who Went Too Far’ which “breathes whisperingly of a house at the edge of a dark wood, and of Pan’s hoof marks on the breast of a dead man,” ‘Negotium Perambulans’, “whose unfolding reveals an abnormal monster from an ancient ecclesiastical panel which performs an act of miraculous vengeance in a lonely village on the Cornish coast” and ‘The Horror Horn’, “through which lopes a terrible half-human survival dwelling on unvisited Alpine peaks”.

We may compare the blameless Hester in ‘The Face’ with the generally thoroughly unpleasant males who bring their nemesis on themselves. Thus in ‘Naboth’s Vineyard’ Ralph Hatchard, a lawyer, sees an opportunity to force the purchase of a house he desires when he recognises its owner, Thomas Wraxton, as a man he defended in court, but was found guilty of embezzlement. Threatened with exposure, Wraxton sells his house to Hatchard and promptly dies of a heart attack. Inevitably, after Hatchard moves into his new house his problems begin. He is haunted by the footsteps of a limping man following him (Wraxton had a limp) and eventually in a terrifying climax he meets his fate, as his brother desperately tries to open his bedroom door, hearing screams from inside. Eventually the door is forced:

"His brother was in bed, his legs drawn up close under him, and his hands resting on his knees, seemed to be attempting to beat off some terrible intruder. His body was pressed against the wall at the head of the bed, and the face was a mask of agonized horror and fruitless entreaty. But the eyes were already glazed in death, and before Francis could reach the bed the body had toppled over and lay inert and lifeless. Even as he looked, he heard a limping step go down the passage outside".

The eponymous hero of ‘James Lamp’ is another man who invites his own destruction, in this case by murdering his wife. She returns to claim him and his body is found with his wife’s hands tightly locked round his throat. She had been dead for several days, he only a few hours.

Both M R James and his great predecessor J Sheridan Le Fanu held the view that for a ghost story to be most effective there should be a certain distance between the present and the period in which the story is set: not a return to the gothic romances of crumbling abbeys, wicked uncles and fainting heroines, but sufficiently far back to avoid intrusions of modernity that may jar with the overall atmosphere, perhaps a return to the age of your grandparents when things may well have been sufficiently different that the suspension of disbelief on which the ghost story so critically depends may be achieved. Indeed commentators on the form wondered whether the ghost story could survive the age of electricity and cars, let alone that of the internet and cheap air travel. These questions have been triumphally answered in the affirmative by a new generation of writers, most notably the Liverpool writer Ramsey Campbell, who find in unvisited parts of the city, such as tunnels and underpasses, the supernatural horrors that were once the province of those much feared attics, cellars and red rooms that feature in so many Victorian and early twentieth century ghost stories.

Unlike many other authors of ghost stories in his time, Benson almost without exception set his stories in the present and was not averse to incorporating elements of modernity. Thus in ‘The Dust-Cloud’ we encounter a ghostly motor car doomed to re-enact the grisly accident its driver caused. In ‘The Confession of Charles Linkworth’ the ghost of a hanged man makes over the telephone to a priest the confession he could not bring himself to make before his execution. In the ‘The Bus Conductor’, a guest in a London town house sees a horse-drawn hearse in the street outside his bedroom window; the driver looks up and beckons to him with the words “Just room for one inside, sir”. No explanation for this appearance is offered the next morning and the guest attributes the episode to a dream. Some time later he is just about to board a London bus, when the conductor, exactly the figure in his vision, calls to him with the same words. Horrified he does not board the bus, which is then subject to a terrible collision with another vehicle. This episode was one of the stories incorporated in the excellent Pinewood Studios film ‘Dead of Night’ (1945), still one of the most frightening films made. For one more example of the incorporation of recent inventions into his stories consider ‘And the Dead Spake’, in which a brilliant surgeon, a latter day Victor Frankenstein, manages to reconstruct speech by inserting a needle into brain tissue and amplifying the sound from the traces etched into the brain by strong emotions, using the equivalent of a gramophone needle. This story anticipates some of the later science fiction where futuristic technology is employed. One of Benson’s strengths as a writer of ghost stories is his ability to use a range of methods by which the dead may communicate with the living, not just the tired medium induced table tapping so prevalent in stories of his time.

In her foreword to the 'Collected Ghost Stories' Joan Aiken makes the point that Benson’s almost exclusively male protagonists tend to come in pairs. Thus we have a first person narrator (who we may take to be the author himself) and a congenial male friend. The two are often spending summer holidays together, with no fixed plan but that of getting away for a while. Settings vary but they are predominantly in England, often on the coast, perhaps Norfolk, Sussex or Cornwall. The conversations between the two are often on the nature of psychical phenonema and how sensitive people can tune in to the impressions left by strong emotions and tragic events in the past. This discussion serves as prelude to the events to follow, which act as exemplars to the theory. It is perhaps in his attempts to ‘explain’ ghosts in these terms that Benson is at his weakest as a ghost story writer. The narrator’s companion is often a professional, such as a surgeon, psychologist or archaeologist, who can interpret the events as they unfold, or as in ‘The Temple’ walk straight into danger. In this story, the narrator and his friend, an archaeologist, contrive to rent a cottage in the middle of a Cornish ‘druidical’ stone circle. The altar stone is actually set amongst the flags of the kitchen floor and it is only the heroic efforts of the narrator against the forces of pagan evil that manage to drag his friend off the altar upon which, with a flint knife, he is attempting to cut his own throat.

Apart from the blameless Hester in ‘The Face’, there are very few women who have central roles in the stories, and where they do they are almost invariably cast in an evil light. ‘Mrs Amworth’ is a typical vampire story and it is not long after she moves into Maxley, West Sussex that strange events begin to happen. Fortunately, the narrator’s friend and neighbour, Francis Urcombe has had relevant experience and, following Mrs Amworth’s death in a motor accident, is able to drive the obligatory sharp implement through her heart, having opened her coffin in the time-honoured manner, thus forestalling an outbreak of anaemia in the village. Another example is the truly terrifying Mrs Acres in ‘The Outcast’, who causes a “sickening of the soul” in those she meets. After burial at sea, following her untimely death, she is washed up on the shore near her village and then, following burial, cannot even be contained in her grave. Malevolent women are also central to ‘The Wishing-Well’, in which a curse is turned back on its originator, and ‘The Bath-Chair’ where a frustrated spinster, in some form of psychic union with her dead father brings about the destruction of her brother who has treated them both so badly. A rare exception is Madge in ‘How Fear Departed from the Long Gallery’, who by her innate sympathy exorcises the ghosts of two murdered children who haunt the Long Gallery after dark and cause death to any who linger there too long and see them. Madge inadvertently falls asleep in the Gallery, but when the children appear her initial terror is replaced by maternal feelings towards the lost children and it is this act of kindness that saves her.

E F Benson’s ghost stories could be subject to the criticism that they are too rounded and predictable. Certainly in many of the stories it is clear from the outset what retribution will be forthcoming and to whom. But Benson is such a master of style and writes with such precision that even with a predictable outcome, the stories are eminently readable and enjoyable. There may be little of the ambiguity of other writers such as Walter de la Mare and, more recently, Robert Aickman, but there are a number of the stories that, even on successive re-reading, still carry that shock factor which all ghost stories require. In the stories will also be found some marvellous descriptions of the English countryside that their author knew so well – its woodlands, coasts and winding lanes and those hidden architectural gems nestling in the shadow of low hills protecting them from the cold winds. The houses are lovingly described in detail as prelude to the events to follow. But Benson is also at home in the suburban setting, where typically the house of interest is at the end of cul-de-sac, so its fortunate inhabitants are not at the mercy of passing traffic, tranquillity only disturbed by those unwelcome visitants who inevitably have a purpose shaped by some past event and seek to bring retribution to the inhabitant.

‘Roderick’s Story’ is unashamedly set at Lamb House in Benson’s fictional Tilling:

"It’s right at the top of the hill, square and Georgian and red-bricked. A panelled hall, dining-room and panelled sitting-room downstairs, and more panelled rooms upstairs. And there’s a garden with a lawn, and a high brick wall round it, and there is a big garden-room, full of books, with a bow window looking down the cobbled street."

As if to make the point more obvious Roderick’s host at Tilling is engaged in writing spook stories – “all about the borderland, which I love as much as you do”.

"And when you get really close to the borderland, you see how enchanting it is, and how vastly more enchanting the other side must be. I got right on to the borderland once, here in this house …. and I never saw so happy and kindly a place."

Roderick takes some of his host’s stories to read:

"The stories were designed to be of an uncomfortable type: one concerned a vampire, one an elemental, the third the reincarnation of a certain execrable personage, and as we sat in the garden-room after tea, he with these pages on his knees, I had the pleasure of seeing him give hasty glances round, as he read, as if to assure himself that there was nothing unusual in the dimmer corners of the room…….I liked that; he was doing as I intended that a reader should."

This passage, in which the author is at his most self-referential, is perhaps a fitting place to leave the spook stories, with, of course, a last glance over the shoulder.

In addition to the four volumes published in Benson’s lifetime, a collection of previously uncollected ghost stories was published as The Flint Knife in 1988, edited by Jack Adrian, and over the period 1988 to 2005 the Ash-Tree Press published all the stories in five volumes, again edited by Adrian.

In his introduction to The Supernatural Omnibus, Montague Summers quotes Madame du Deffand, who when asked if she believed in ghosts, replied “No, but I am afraid of them” - a perfect frame of mind, I would suggest, in which to approach E F Benson’s ghost stories.

(This article first appeared in 'Dodo', the journal of the E F Benson Society.)

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPad