The number of books that can be read in the average lifetime is necessarily limited; the urge to collect more books continues undiminished for many years. Therefore choices have to be made as to which books to read now and which can be safely deferred for a few years longer. This choice becomes particularly acute when the books in question are long, and by long I mean of the order of 1,000 pages or more.

However, the rewards of total immersion in a long book can be incalculable, as you are sucked into the world of its characters and the book you are reading seems to be the only book you have ever read. I want to write about several such books that have made a deep impression on me and to indicate others on the shelves as yet unread.

"War and Peace" has become almost a catch-phrase or generic name for books that over-awe by their length and reputation. I bought my copy in W H Smith in Chester in the summer holiday after completing my first degree. It seemed a good use of time before commencing further studies leading to a PhD. And so it was; from the very beginning I was totally absorbed in the events of the time and the lives of the characters, Pierre, Natasha, Nicholas, Andre, Sonya and the rest, so that when the final page was turned there was a genuine feeling of loss. I have read the book twice since that first reading, in the same Louise and Aylmer Maude translation, but it is that first encounter with Tolstoy's brilliance that has left the permanent impression.

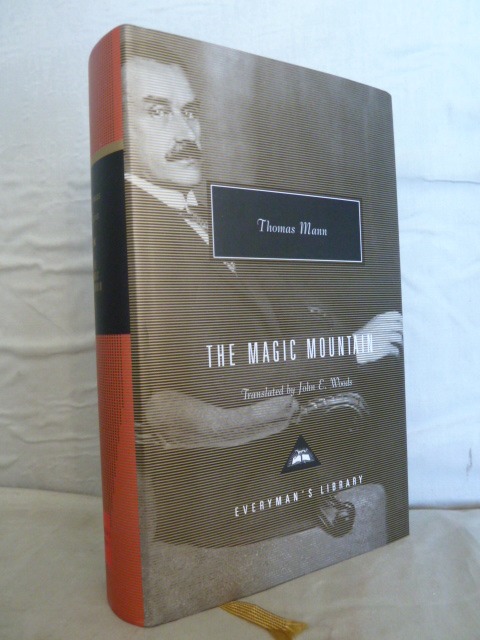

That was some 40 years ago, but it was last early last year that I finally got round to Thomas Mann's "The Magic Mountain". I expected this to be a "difficult" book, but I was wrong. For a few weeks I lived with Hans Castorp in that sanitorium, high in the Alps. With Hans I took long walks and rest cures, learnt how to wrap myself in a blanket and followed him to dinner, hoping to avoid the 'bad Russian' table. With Hans, I was a fascinated, if somewhat perplexed, listener to the interminable debates between the Jesuit Naphta and the rationalist Settembrini, that are only brought to a conclusion when the former blows his own brains out in their duel. There was a sadness when I finally left the sanitorium with Hans to face an uncertain future as the Great War took its toll.

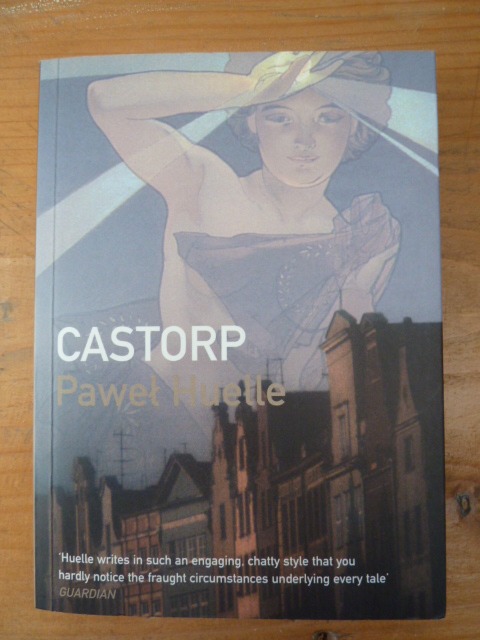

Early last year we were in Cracow and in the excellent American Bookstore there I found a copy of Pawel Huell's "Castorp". This is a short book, but is a sort of prequel to "The Magic Mountain", as it tells the story of Hans Castorp in Gdansk, where he was studying marine engineering, a period briefly alluded to in Thomas Mann's book. This book is so well written that for a short time I was taken back to Castorp's world.

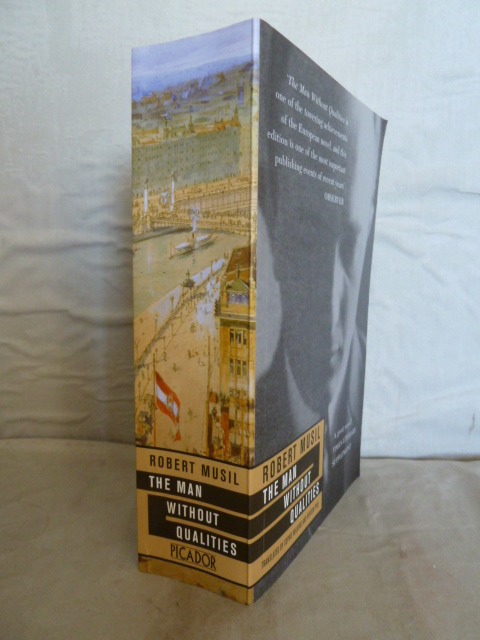

Another central European classic is Robert Musil's "The Man Without Qualities". It was its marvellous opening line - 'A barometric low hung over the Atlantic' - that attracted me to this book when I picked it off the shelf in the sadly now long gone Borders bookstore in Preston. The setting is Vienna a year or so before the outbreak of the First World War and, with the eponymous hero, Ulrich, I attended the endless receptions and meetings to plan the celebrations to mark the 70th anniversary of the accession of the emperor Franz Josef. It is all so pointless, which I suppose is the point of the book.

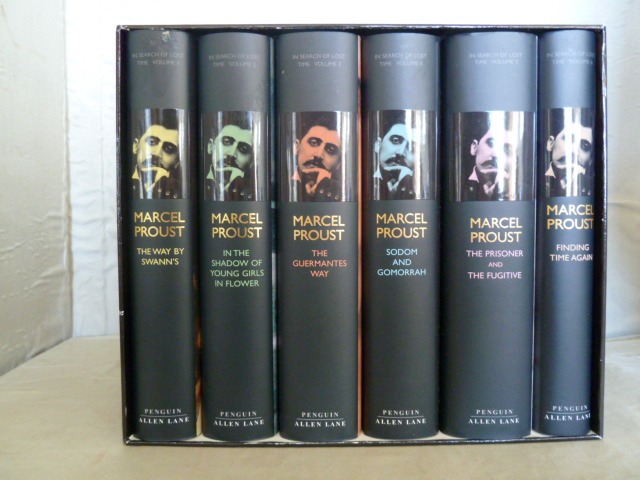

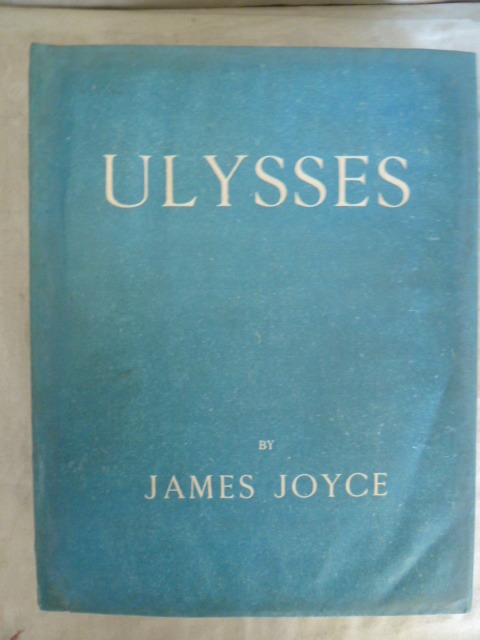

Proust's "In Search of Lost Time" is really several books, but it is better read as one long work, a task I completed one summer. By the end I felt I knew Swann better than those in whose company he then mixed. Time passes in these books; by contrast the action of James Joyces' "Ulysses" takes place in but a single day, but what a day! From the outside perhaps not eventful, but from the perspective of Leopold Bloom a day packed with incident and adventure, best experienced by turning up in Dublin on Bloomsday and just going with the flow.

"Gone with the Wind", "Les Miserables", "Middlemarch", the list could go on, but it is now time to pay homage to those long books as yet unread on our shelves. There they perch, like 'Angry Birds', waiting to sink their claws into me should I be so reckless as to disturb their slumber

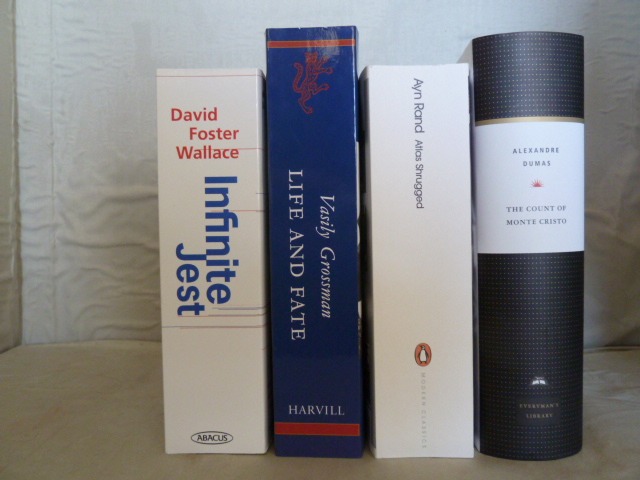

A quick scan of the paperback shelves reveals the following:

"Infinite Jest", by David Foster Wallace (for debunking the American Dream);

"Atlas Shrugged", by Ayn Rand (for learning about Objectivism);

"Life and Fate", by Vasili Grossman, set in war-time Stalingrad (not much fun there);

"The Count of Monte Cristo" (for when I am falsely accused, whilst planning my daring escape from prison).

There they are, some 5,000 pages awaiting my attention, but first I will read some haiku.

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPad