Thomas West's "Guide to the Lakes", first published in 1778, advised the traveller on where to go and what to see and, in particular, Thomas West identified 'Stations', or specific locations from which the most sublime views were revealed.

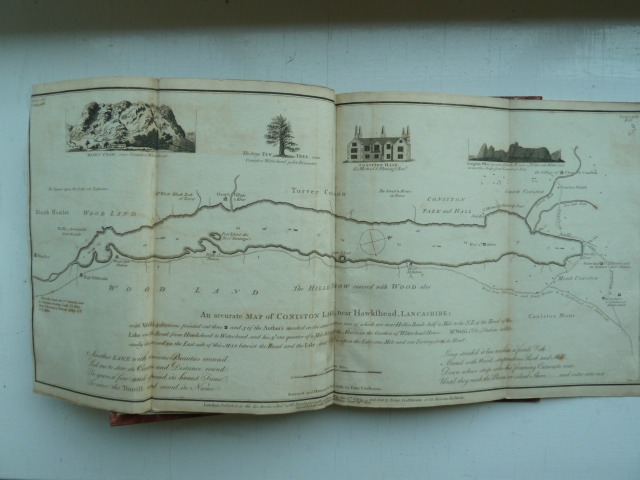

Further help for the traveller was provided by way of a set of maps of the lakes published in 1794 by Peter Crosthwaite. These maps marked the Thomas West stations and provided helpful advice on what could be seen from them.

A helpful geocacher has provided grid references for the Thomas West stations as part of a geocaching puzzle so the task of finding the stations is even easier than in Thomas West's day, when travellers were advised to look for such markers as a picturesque ash or a distinctive boulder to guide them on their way.

Thus educated, we set off with GPS in hand to visit the four stations on Coniston Water. Actually, there are only three stations that can be visited on foot, the fourth being actually on the lake. The first three are all on the east side of the lake, looking over the lake to the grand prospect of Coniston Old Man and Dow Crags.

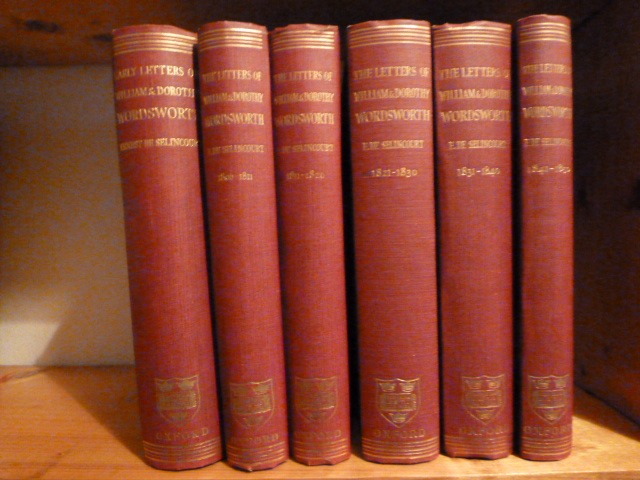

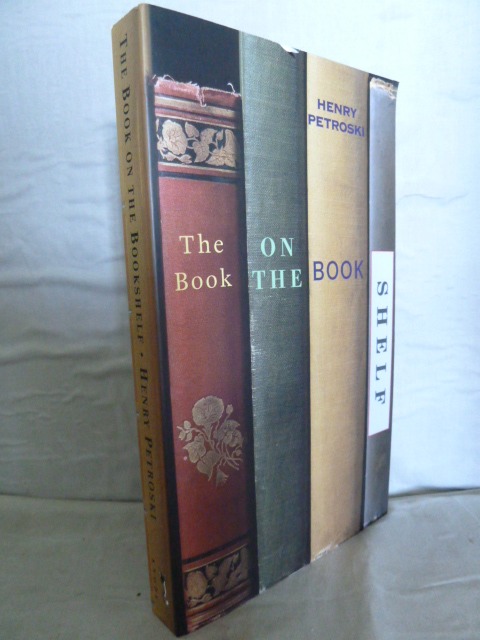

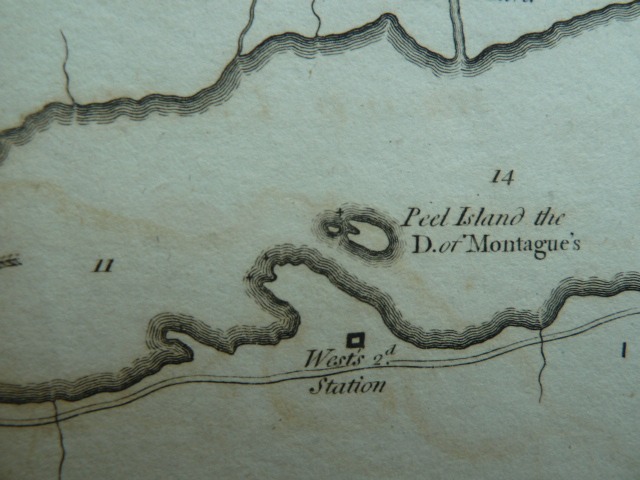

The Stations are identified on Crosthwaite's map as shown below:

It was a beautiful Saturday morning in spring and we anticipated a calm progression following the narrow road around the east side of the lake and marvelling as the vistas opened out in front of us. However, the sublimity of our experience was somewhat jarred as the day we chose was that of the "Coniston 14 plus", a road race being run by several hundred around the lake. Weaving our way through the runners we did manage to reach the three stations.

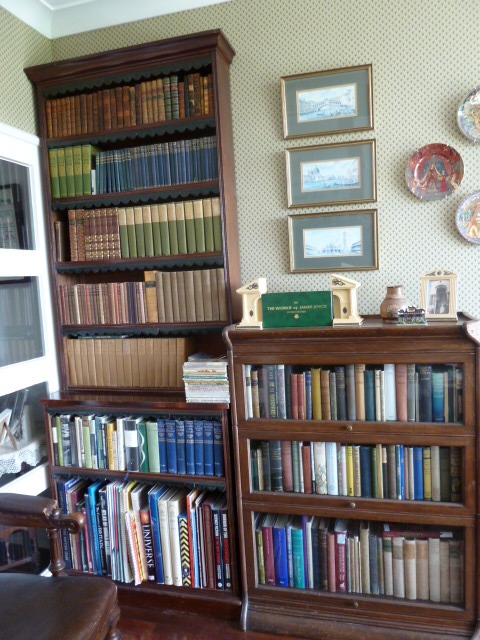

Station 1 is located at Nibthwaite at the southern end of the lake. Unfortunately, there is now no public access to the lakeside at this point and so we hurried on to Station 2. This is situated on National Trust land adjacent to Peel Island and the station is reached after a short walk through woodland, which leads to an elevated position from which magnificent views of the lake and Coniston Old Man are obtained.

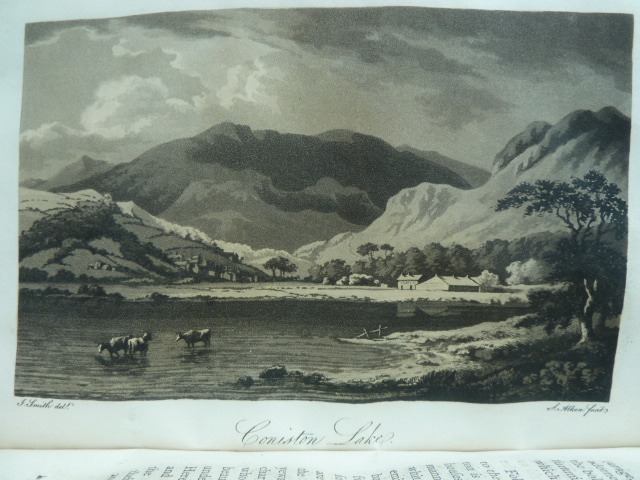

The views today may be compared to those shown in an aquatint in Thomas West's "Guide".

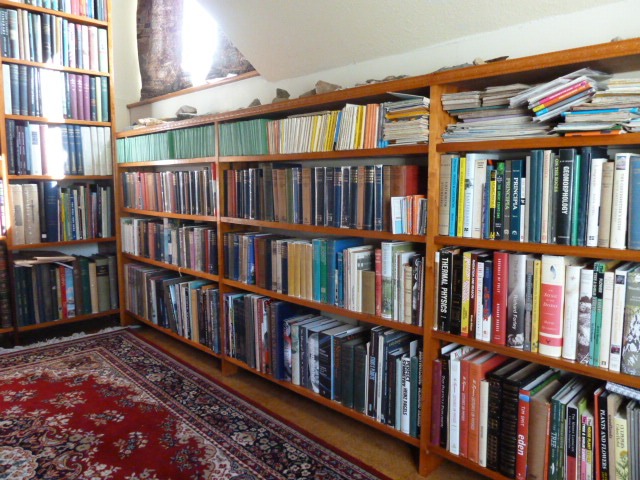

Station 3 is nearer the northern end of the lake and is again on National Trust land. This station is near to Brantwood, the home of John Ruskin from 1872 to 1900, who supposedly bought the house on the strength of its situation without having actually seen it. Maybe he had a copy of Thomas West's "Guide".

This view may be compared with that from a similar point given in J B Pyne's "Lake Scenery of England" (1859):

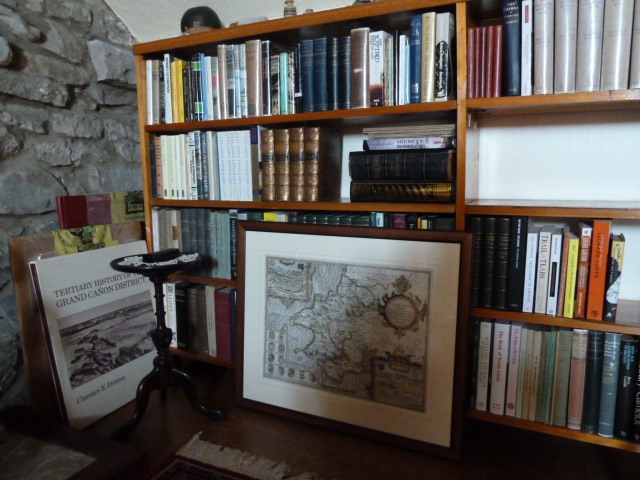

and with the view from Brantwood:

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPad