In order of reading, these are the books I have read in 2012, with brief comments and my own star ratings.

'Our Mutual Friend', Charles Dickens, ****, excellent mystery novel with good characters and atmospheric descriptions.

'Death and the Future Life in Victorian Literature and Theology', Michael Wheeler, *****, fascinating account of the Victorian view of death, judgement, Heaven and Hell, using, amongst others, as examples 'Our Mutual Friend' and 'In Memoriam'.

'Little Dorrit', Charles Dickens, ****, again an excellent novel, full of incident and characterisations.

'The Grid Book', Hannah B Higgins, ***, descriptions and history of various grids, from bricks to printing, gridirons, nets and screens.

'American Fantastic Tales', Volume 1, Peter Straub (ed), ****, covers the period from Poe to the Pulps, a good selection.

'Dombey and Son', Charles Dickens, ****, Florence Dombey wins through against stern father. Child dearh of Paul Dombey as sentimental as you can get, but very powerful.

'Dickens: a Biography', Claire Tomalin, *****, superb biography, sets out her thoughts on the Nelly Ternan relationship.

'The Infinity of Lists', Umberto Eco, *****, wonderfully illustrated book with essays on various kinds of lists in literature, from Homer's list of ships in 'The Iliad', to Calvino's 'Invisible Cities'.

'The Arcades Project', Walter Benjamin, ****, massive compilation of notes from Benjamin's alternative history of Europe, as evinced by the Parisian arcades.

'Walter Benjamin's Archive', ***, catalogue of fragments from Benjamin's collection, with good introductory essay.

'Le Fanu's Ghost', Gavin Selerie, ***, overview of links between the Sheridans and J Sheridan Le Fanu, with extracts from books, poems etc.

'Darwin - a Life in Poems', Ruth Padel, ****, well annotated set of poems by Darwin's great grand-daughter tracing Darwin's life.

'The Old Curiosity Shop', Charles Dickens, ****, the dearh of Little Nell possibly the best moment in this very fine novel.

'I am Providence', S T Joshi, ****, massive two volume biography of H P Lovecraft', full of detail.

'American Fantastic Tales', Volume 2, Peter Straub (ed), ****, covers the period from the 1940s to the present; particular favourite 'Stone Animals' by Kelly Link.

'Curfew and other Eerie Tales', Lucy M Boston, ***, competent collection of ghost stories, the title story the best.

'David Copperfield', Charles Dickens, ****, the early chapters are the best, the relationship between David and Agnes becoming tedious as the book nears its conclusion.

'Strange Epiphanies', Peter Bell, ****, atmospheric supernatural stories, evoking the spirit of place with suitably nasty endings.

'Empire of Shadows', George Blake, ****, the epic story of Yellowstone, covering its exploration and development.

'Chief Joseph, Guardian of the People', Candy Moulton, ****, good history of the Nez Perse indians and their great leader, who finally surrendered after a 1500 mile retreat from the Wallowa Valley in Oregon to near the Canadian border.

'Lost Places', Simon Kurt Unsworth, ***, interesting ghost stories, but marred in places by poor style and far too explicit content.

'The Lakotaa and the Black Hills', Jeffrey Ostler, ***, good account of the relationship between the Lakota Sioux and the Black Hills and their continuing fight to regain their sacred land.

'Hard Road West', Keith Heyer Meldahl, *****, superb account of the geology along the gold rush trail to California. Well illustrated with many maps and cross sections.

'The Best Read Man in France', Peter Briscoe, ***, a bookseller in LA fights to prevent a collection of rare books being broken up to be digitised at the library he sold them to.

'Magic for Beginners', Kelly Link, ***, strange stories with unusual events and references back to Lovecraft and other fantasy writers.

'The Dewey Decimal System', Nathan Larson, **, crime novel set in a post terrorist New York. Violent and poorly written.

'The Pale King', David Foster Wallace', ****, unfinished novel about work in an IRS examination center in Peoria, Illinois. Full of detail about bureaucratic procedures, with some brillianr passages.

'The Fountainhead', Ayn Rand, ****, the struggles of architect Howard Roark against the forces of concensus in architecture. Roark battles to preserve his artistic integrity.

'Anthem, Ayn Rand, **, dystopian novel about a society in which all individuality has been subsumed to the collective will and the word 'I' does not exist. The hero breaks free.

'A Certain Slant of Light', Peter Bell, ****, good ghost stories in the M R James tradition with varied setttings.

'Reading Joyce', David Pierce, ***, helpful guide by a former teacher of Joyce, which includes some autobiographical material as well as good criticism.

'Paradise Lost, Smyrna 1922, the Destruction of Islam's City of Tolerance', Giles Milton, ****, harrowing account of the history of Smyrna culminating in its burning by the Turks.

'Safe Area Gorazde', Joe Sacco, excellent graphic novel about events in Bosnia between 1990 and 1995. The author spent time in the city after the conflict and talked with many survivors. The author is scathing about the role of the UN peacekeepers.

'Bleak House', Charles Dickens, ****, re-read and again much enjoyed. Esther Summerson ultimately becomes tiresome.

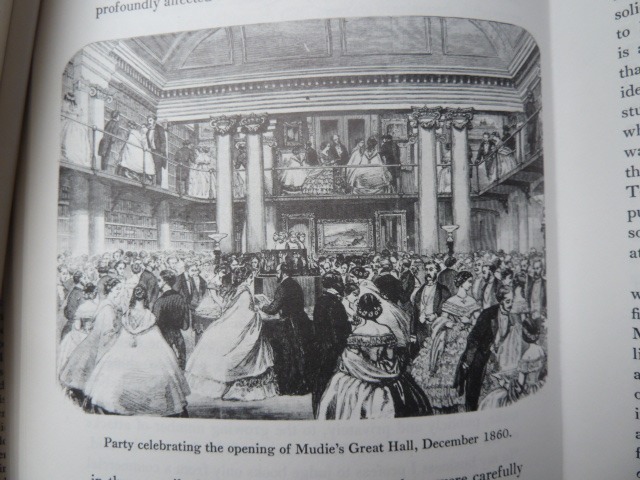

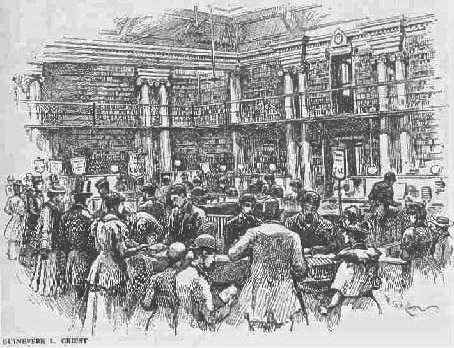

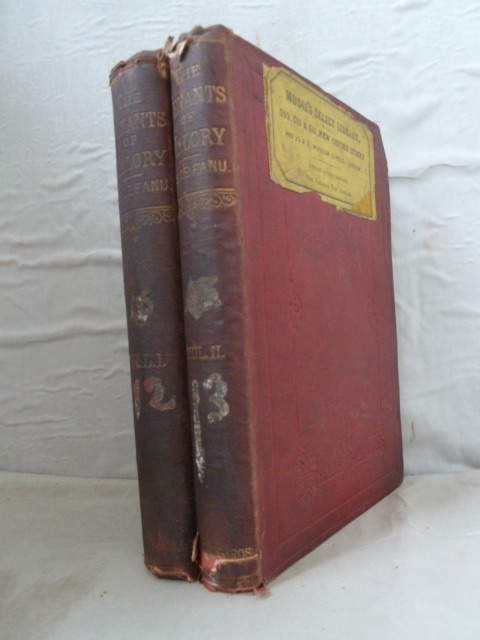

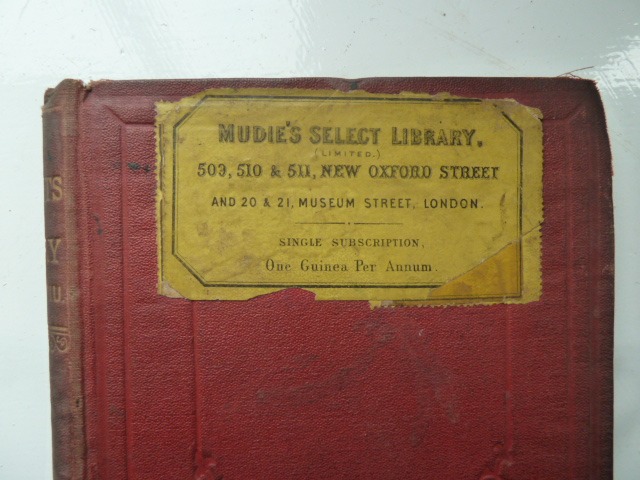

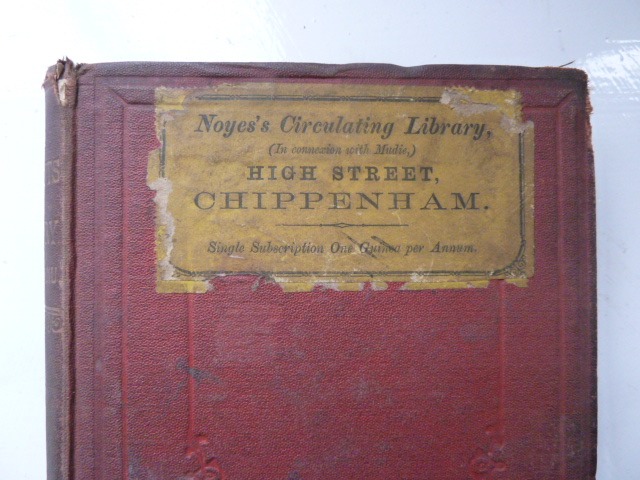

'Mudie's Circulating Library and the Victorian Novel', Guinevere L Girest, *****, excellent history of Mudie's who dominated book distribution from the 1840s to the 1890s and whose insistence on the 3 volume novel set the fashion for many writers.

'The Haunting of Lamb House', Joan Aiken, ***, tells the story of three inhabitants of Lamb House at Rye, the best part being that about Henry James written in his style.

'E Nesbit's Tales of Terror', Edith Nesbit, good ghost stories, the best being 'Man Size in Marble'.

'Three Miles Up and other Strange Stories', Elizabeth Jane Howard, ****, the title story of a canal journey into a strange landscape is the best, but all are well written.

'We Are for the Dark', Robert Aickman, ****, collaboration between Aickman and Elizabeth Jane Howard, with each contributing three stories. Aickman's 'The Trains' is the best.

'Adventures of Augie March', Saul Bellow, ***, chronicles the early life of Augie, born in Chicago as he passes from job to job and woman to woman. Some good passages, particularly when the commonplace events of today are contrasted with Greek heroic legend, but I would not be tempted to read more Bellow.

'Dark Entries', Robert Aickman', ****, good atmospheric strange stories in which individuals find themselves in strange threatening locations. The best is 'Bind Your Hair' in which a woman becomes embroiled in pagan rituals in the Northamptonshire village her fiancee has taken her to to meet his parents.

'Powers of Darkness', Robert Aickman, ****, the best story is 'The Wine Dark Sea', set on a Greek island.

'Sub Rosa', Robert Aickman, ****, more atmospheric stories, particularly good are 'Never Visit Venice' and 'The Houses of the Russians'.

'Alone in Berlin', Hans Fallada, ****, a powerful novel set in 1940s Berlin as Otto Quangel and his wife mount their own resistance campaign against Hitler.

'Cold Hand in Mine', Robert Aickman, ****, another good collection, with the best story 'The Hospice'.

'Tales of Love and Death', Robert Aickman, ***, one or two very weak stories such as 'Growing Boys', but 'Residents Only' and 'Wood' compensate.

'Illusions', Robert Aickman, ***, the best story is 'The Fetch'.

'The Attempted Rescue', Robert Aickman, ***, Aickman's account of the first 30 years of his life. A bit self-absorbed.

'A Great Idea at the Time', Alex Beam, ****, a very good book about the Great Books project of the University of Chicago in the 1950s.

'Double Fold', Nicholas Baker, ***, a book about libraries and the assault on paper in the latter part of the 20th century. Very hard-hitting against the Library of Congress and the British Library.

'Nazi Germany and the Jews Vol 1, The Years of Persecution 1933-1939', Saul Friedlander, ****, a detailed history of this period and showing the indifference of all European nations to Hitler's policies.

'The Beetle', Richard Marsh, ***, a supernatural thriller that gets a bit tedious at times.

'18 Bookshops', Anne Scott, 3***, short essays on bookshops, both old and contemporary.

'Nazi Germany and the Jews Vol 2, The Years of Extermination 1939-1945', Saul Friedlander, ****, the conclusion of this massive study.

'Dolly - A Ghost Story', Susan Hill, **, a rather poor story.

'The Quark and the Jaguar - Adventures in the Simple and the Complex', Murray Gell-Mann, ***, a study of complex adaptive systems that loses its way a bit. Good discussion of quantum mechanics.

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPad