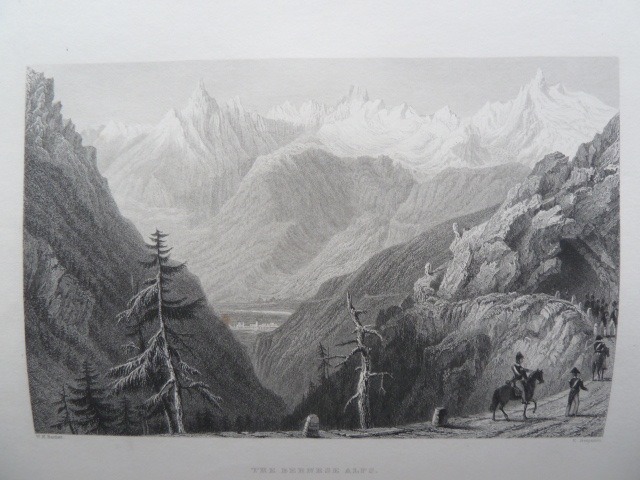

Visit any shop selling topographical prints and it is almost certain that before long you will find a steel engraving with the name of W H Bartlett on it. Indeed so ubiquitious is this name that it seems impossible for one person to have travelled so far to draw so many views, particularly since this apparently frenetic activity was compressed into a relatively short working life. Unlike some other artists (including Turner) who 'improved' in their studios drawings made on the spot by others, Bartlett drew the scenery that he saw and his views could be directly used by the engraver. This gives his illustrations the benefit of his actual observation of the scene, but entailed a burden of travel that eventually took its toll.

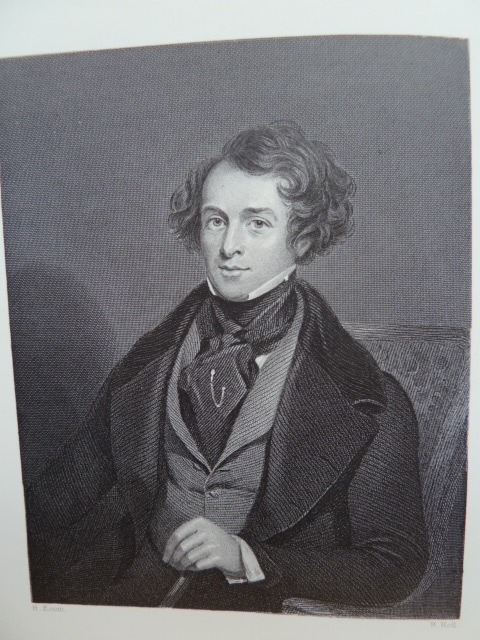

William Henry Bartlett was born in Kentish Town in 1809 and died in 1854 returning from one of his many overseas trips. His life reveals the almost intolerable pressure put on working artists by publishers anxious to meet the rapacious demand of the public for topographical views during the 1830's and 1840's, an age well before photography rendered such depictions of scenery obsolete.

Yet the result of this activity is a series of wonderful books, embellished with finely produced steel engravings, that form a valuable record of much of the civilised world in the early years of Victoria's reign.

An excellent survey of steel engraving is contained in Basil Hunnisett's 'Steel-engraved Book Illustration in England', which describes how the introduction of improved mechanised printing processes in the early years of the 19th century enabled mass production leading to a boom in the production of books containing steel engravings in the period 1825 to 1845.

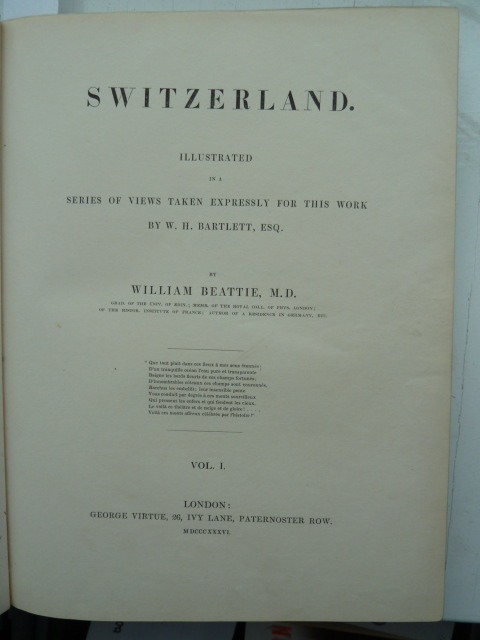

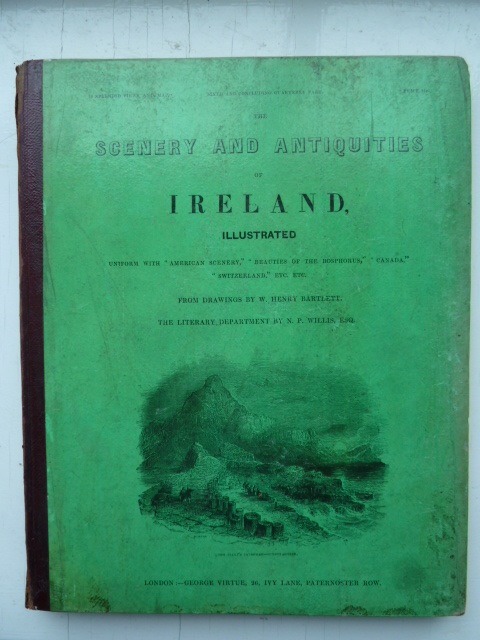

William Bartlett served as an apprentice to the famous draughtsman John Britton for the seven years up to 1829 and then found employment with George Virtue, who had established a publishing house in London in 1819, moving his offices to the Paternoster Row area in 1829. It is probably fair to say that the partnership between Virtue and Bartlett made the former's fortune as, in this period, Virtue issued over 100 illustrated books and produced some 20,000 engravings, using many of the leading artists and engravers of the day. However, of these artists it is Bartlett who must claim pre-eminence.

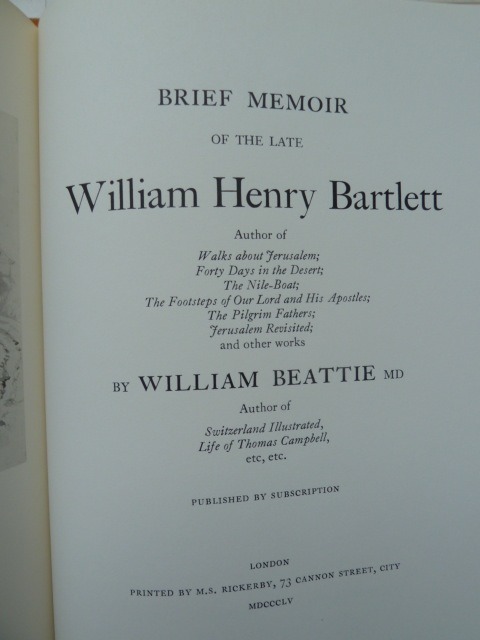

Bartlett's early work for Virtue consisted of illustrations for two county histories - Irelands 'Kent' and Wright's 'Essex'. However, his first commission abroad, in the company of the writer and doctor William Beattie (who became a close friend), led to a spell in Switzerland in 1832-3 where his drawings form the 108 plates in the two volume work (one of Bartlett's best) published in 1836.

In Switzerland, Bartlett suffered a fever due following a cold caught working in the mountain snow and was nursed by his young wife, Susanna.

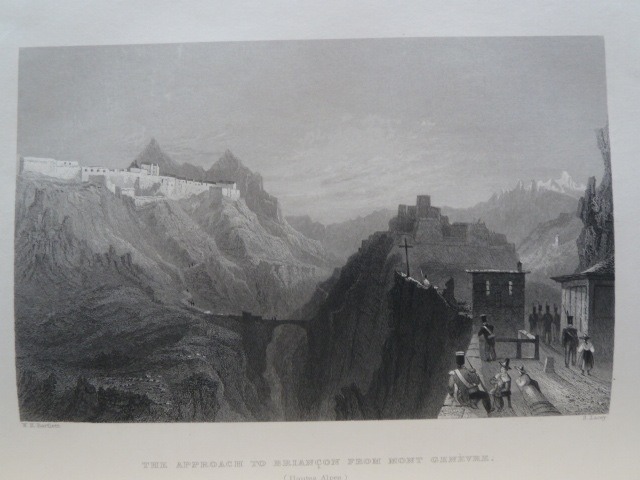

1834 finds Bartlett in the middle east providing illustrations for 107 plates for a 3 volume work on Syria and the Holy Land, then in early 1835 he is sent to Piedmont for illustrations to Beattie's 'Waldenses', which contains some lovely depictions of southern France and northern Italy. Later that year he is drawing for Van Kempen's 'Holland and Belgium'.

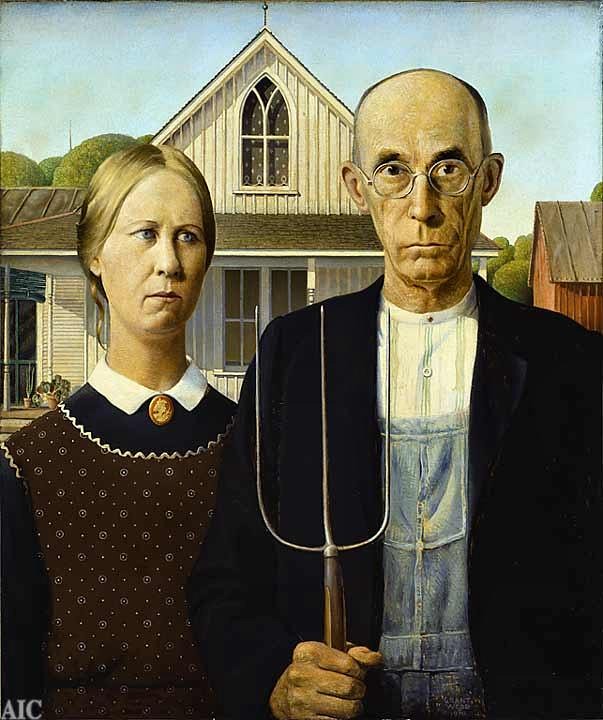

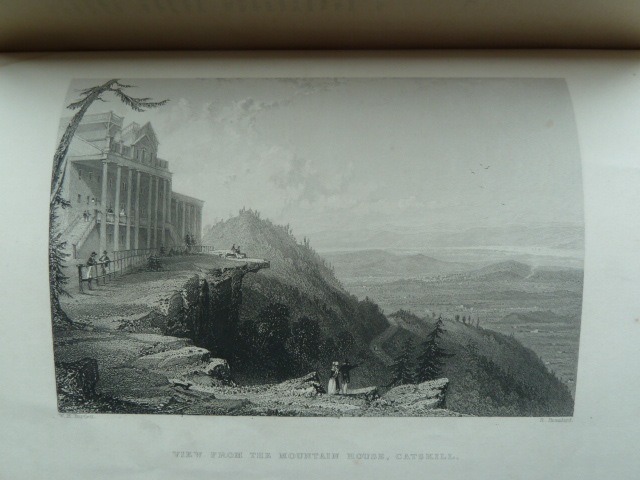

One of Bartlett's most famous books is 'American Scenery', with text by N P Willis, the illustrations for which Bartlett produced in his stay in the New World from mid 1836 to mid 1837.

In this period, in addition to the usual eastern sights, Bartlett and Willis visited Niagara and toured Wyoming.

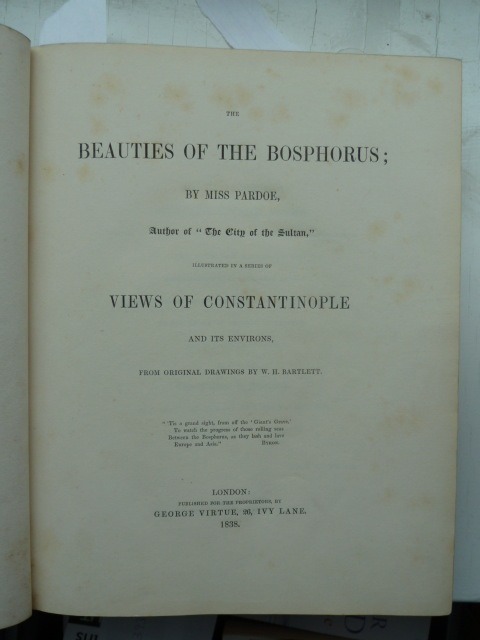

No rest for the wicked, as immediately on his return, Bartlett was despatched to the middle east to illustrate Julia Pardoe's 'Beauties of the Bosphorus', another lovely book published in 1839.

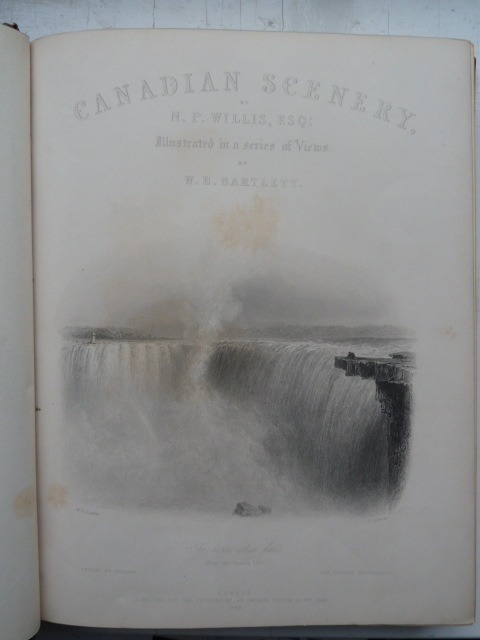

Most of 1839 was spent in Canada drawing for Willis's 'Canadian Scenery', published in two volumes in 1842. Bartlett's activities now become frenetic back in Great Britain as he provides illustrations for Beattie's 'Scotland Illustrated', Finden's 'Ports, Harbours and Watering Places of Great Britain' and Coyne and Willis's 'Scenery and Antiquities of Ireland' (1842).

A further trip to America was followed by a journey up the Danube to the Black Sea in 1842 to illustrate Beattie's 'Danube'. This trip culminated in a visit to Jerusalem where he provided illustrations for his own book 'Walks about the City and Environs of Jerusalem'. Bartlett was back in the Near East again in 1845 to collect material for another of his books, 'Forty Days in the Desert, on the Track of the Israelites' (1848).

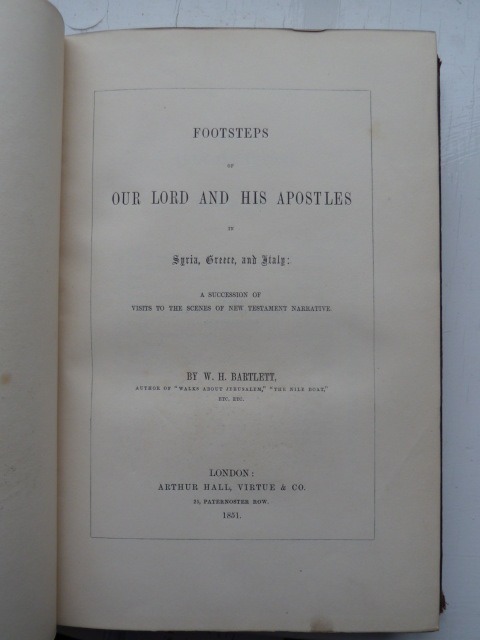

After this came a calmer spell as he sought to recover his impaired health, with spells at home and tours of Wales and Yorkshire leading to him becoming editor of 'Sharpe's London Magazine', a post he held from 1849 to 1852. He did, however, make further trips to the Meditteranean (1850) and Sicily (1851) resulting in his 'Pictures from Sicily' and his most popular work 'Footsteps of our Lord and his Apostles in Syria, Greece and Italy' (1851).

Bartlett made his fourth visit to America in 1852 to prepare material for his historical work 'The Pilgrim Fathers'. Then it was Jerusalem in 1853, leading to 'Jerusalem Revisited' (1854).

In 1854 Bartlett set off, reluctantly, on what would be his last trip, to explore Asia Minor. He reached Smyrna in August, but left in the wake of a cholera epidemic. Setting off for home (with 50 drawings completed) on the French mail steamer Egyptus he became ill, dying on 13 September and being buried at sea. His wife and children were saved from absolute poverty following the publication of 'A Brief Memoir of William Henry Bartlett' by the faithful Beattie in 1855 and the granting of a pension by the Prime Minister for Susannah.

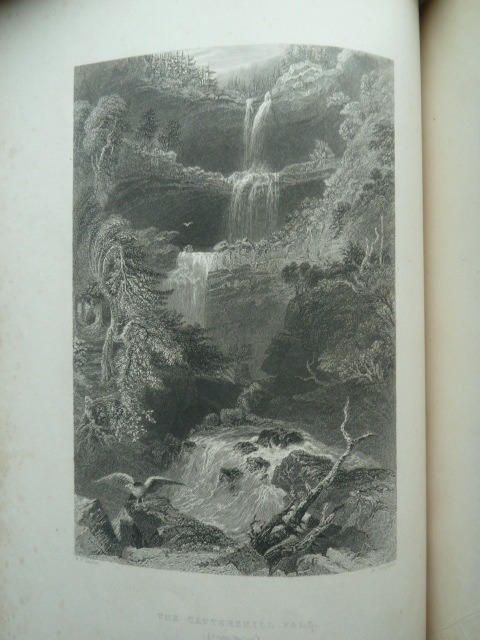

Bartlett had led a life of unremitting effort, suffered greatly from depression, and considered himself inferior to his contemporary landscape artists, such as Crome, Cox, Cotman and Turner. However, he shared their passion for the picturesque and sublime and was familiar with the works of the romantic poets. His illustrations owe much to the wildness of Salvator Rosa, but also to the idealised forms of Claude and Poussin.

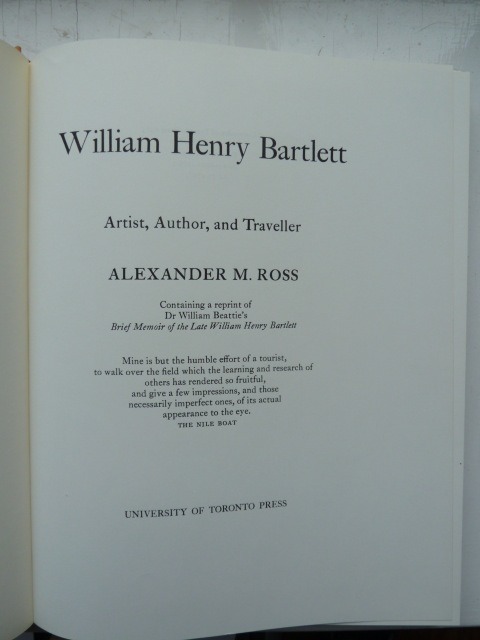

In his excellent essay on Bartlett, Alexander Ross, draws parallels between specific Bartlett illustrations and the works of these earlier masters. Bartlett's Scenes are often populated with local people, in appropriate peasant costume and both grand and vernacular architectural features are depicted. Perhaps his most lasting legacy, however, will be the scenes of America and Canada, that contributed to introducing the New World to the Old World.

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPad