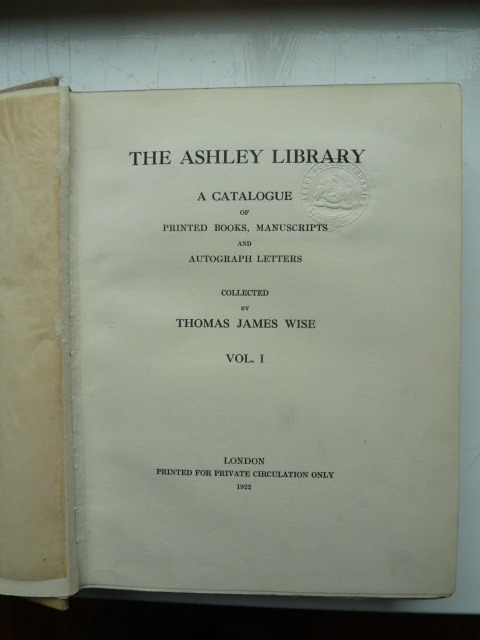

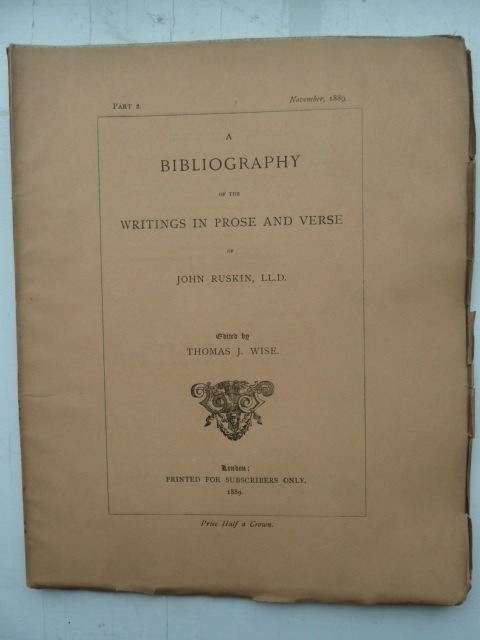

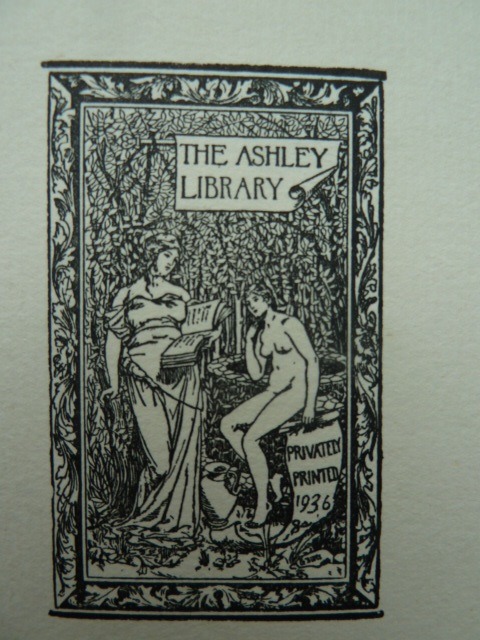

One of the greatest catalogues of a private library is the Ashley Library Catalogue, listing in 11 handsome volumes the collection of Thomas J Wise, one of the foremost bibliographers and collectors of his day.

The first volume of Wise's catalogue was published in 1922; the last in 1936.

In these volumes, Wise's library of some 7,000 volumes is described in detail with many photographs. This library was perhaps the greatest collection of classic English literature ever assembled by a private individual, being particularly strong on restoration drama, romantic poets and nineteenth century writers. Many manuscripts were contained within the collection, which was very strong on Browning, Shelley, and Swinburne. The collection also contained Bronte manuscripts and letters, which Wise had procured from Charlotte's husband Arthur Bell Nicholls, at the time living in his native Ireland, in one of his great collecting coups.

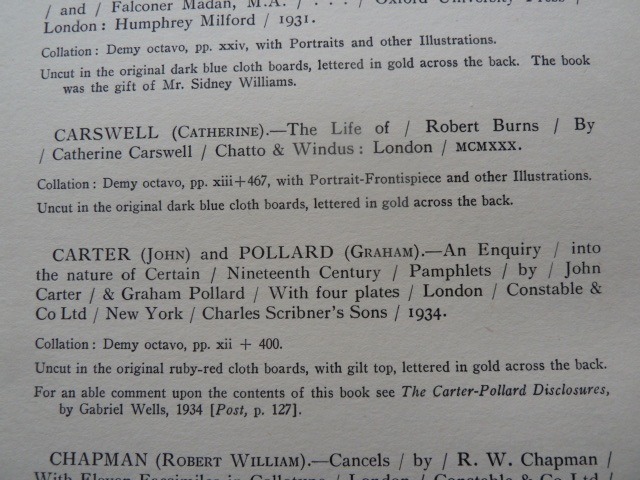

It is on Page 52 of Volume XI (containing later additions to the collection) that we find perhaps the most astonishing item in the whole catalogue.

This is a book published in 1934 with the hardly attention-grabbing title of "An Enquiry into the Nature of Some Nineteenth Century Pamphlets" by the, then relatively little known John Carter and Graham Pollard. This book threw a bombshell into the normally sedate world of bibliographical scholarship with its unmistakable message that the most respected bookman of the day, Thomas J Wise, member of the Roxburghe Club and eminent bibliographer of Ruskin, Swinburne, Pope, the Brontes and others, was a common forger. That Wise included this exposé in his catalogue is tribute either to a monumental ego or to an inability to distinguish truth from fiction in his own life.

What Carter and Pollard set out to show in their book was that a number of rare pamphlets which had entered the market, mainly via the main auction houses, in the early twentieth century were, in fact, forgeries and had been printed not at their stated dates of early to mid nineteenth century but no earlier than the late nineteenth century. It was also shown that the source and authentication of many of the pamphlets could be traced back to Thomas J Wise.

The first of Wise's forgeries appeared in 1887 and over the next 20 years or so Wise and his collaborator Harry Buxton Forman (editor of the definitive edition of Shelley's works) produced some 100 forgeries. The particular genius of Wise and Forman was to produce works that could quite reasonably have been printed at their stated dates, but nevertheless had not been, the classic example being Elizabeth Barrett Browning's "Sonnets from the Portugese", where letters between Elizabeth Browning and Mary Mitford suggest the possibility of an early private printing anticipating the first published edition.

Wise dutifully produced the missing volume, dating it 1847, some 50 years earlier than its actual date of production. Then, as the most eminent bibliographer of the day he could provide impeccable authentication of the pamphlet.

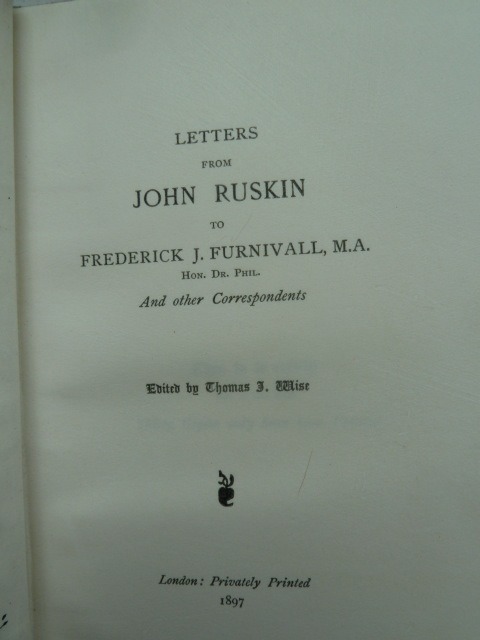

The production of forgeries dried up in the early twentieth century but Wise (who held a stock of the print runs) could judiciously release copies on to the market (normally via third parties totally unaware of their true nature) and pocket the profits.

Wise's malpractice could have been exposed some 30 years earlier, when Cook and Wedderburn were compiling their monumental 39 volume Library Edition of the works of John Ruskin. They questioned the authenticity of some 'early' Ruskin pamphlets, such as "The Scythian Guest" and "The Queen's Gardens". However they stopped short of attempting an identification of the true source of these publications.

Carter and Pollard's work provides a riveting story of bibliographic detection, bringing to bear a variety of arguments, such as type faces that had not been cut at the stated date of publication and the use of wood pulp paper, when only rag paper should have been available. They also noted the remarkably fine condition of the pamphlets, belying their supposed age. The argument that the pamphlets were forgeries was irrefutable; the identification of Wise as the forger was not explicitly made but was abundantly clear to the discerning reader.

The scandal hit the national dailies, with Wise writing a brave letter of defence to "The Times". The great and the good of book collecting, such as Edmund Gosse, leapt to his defence, challenging the young upstarts Carter and Pollard. But all to no avail; Wise's reputation was irretievably ruined and he died three years later.

It is all a sad commentary on the obsessive desire of collectors to acquire unique and precious items for their collection. Wise was fully acquainted with this obsession and tapped into it ruthlessly. The idea probably began when, on behalf of the Shelley Society, Wise and Forman produced facsimiles of genuine Shelley pamphlets in limited numbers for Society members. These were printed by the respectable firm of Richard Clay at Bungay in Suffolk and must have looked very much like their genuine counterparts. From this, it was perhaps a small step to extend this practice to produce the forged pamphlets, Wise and Forman's unrivalled scholarship being able to provide all the fake provenance needed for the hungry collector. There is no evidence suggesting the printers were part of the plot; they just printed as demanded by a pillar of the literary establishment.

Wise's methods were audacious. He would, for example, anonymously place a pamphlet at auction and then commission two separate bidders (unknown to each other) to bid for the pamphlet on his behalf. The high price made would guarantee notice of the 'find' in the book collecting world and Wise would, of course, be called on to authenticate the item, all the time having a box full of other copies at home. Over subsequent years these other copies could then be released onto the market to satiate the desire of collectors for these rare and unique items.

Since Carter and Pollard's work was published, studies into the extent

of Wise's activities have continued.

In 1983 Scolar Press published in two handsome volumes a reprint of the original "Enquiry" and a sequel to the enquiry by Nicholas Barker and John Collins. In the sequel the story is brought up to date and the authors confirm the number of Wise/Buxton forgeries at of order 100. With minimal printing costs and print runs of possibly 20 to 30 per pamphlet, the stock of forgeries represented an extremely lucrative venture for the pair as they were drip fed into an all too gullible market for rare books.

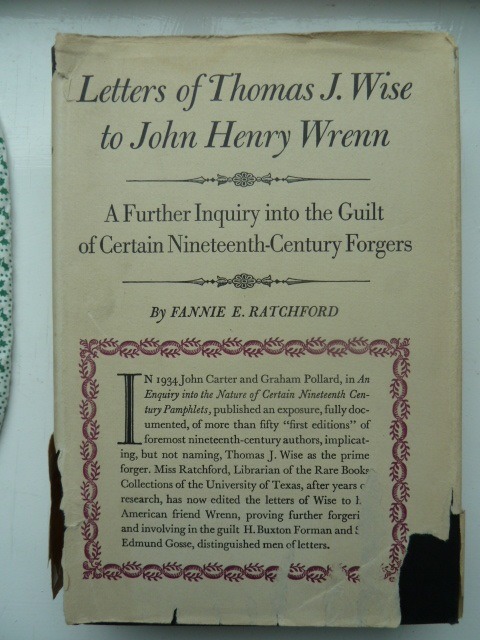

One of Wise's most famous victims was one of the great American collectors, the Chicago business man John Henry Wrenn. Over many years Wise procured rare books for Wrenn, including up to 100 examples of forged pamphlets, bought in good faith by Wrenn. The Wrenn collection of some 6,000 books was the firsr rare book collection acquired by the University of Texas at Austin.

The letters between Wise and Wrenn were published in a handsome volume in 1944, edited by Fannie E Ratchford, Librarian of the Rare Books Collection at the University of Texas and they make fascinating reading, as Wise tempts Wrenn with yet one more amazing newly discovered Shelley, Ruskin or Browning pamphlet. Of course, without Wise's unmatched bibliographical knowledge, Wrenn could never have assembled such a wonderful collection of genuine rarities and Texas would be all the poorer. And, of course, Wrenn died never knowing the extent to which he had been cheated by his friend. As time passes, attitudes change and, perhaps not unsurprisingly, to modern eyes the inclusion of so many Wise forgeries in the Wrenn Library adds considerably to its lustre.

Following Wise's death his library was purchased by the British Library (where it still resides) for £66,000. It was only then that another, perhaps even more unsavoury, practice of Wise was revealed. It was found that dozens of defective books in Wise's collection originally missing pages or plates had been completed by the removal of the relevant pages from the copies in the British Museum Library. The equivalent copies in the British Museum were found to have been skilfully plundered to complete the Ashley Library copies. Checks at Austin, Texas showed that a not inconsiderable number of volumes purchased by Wrenn had been similarly completed with stolen leaves. Of course, with his reputation, Wise would have had unlimited access to the remotest rare book stacks in the British Museum and armed with razor blade and ruler could carry out his thefts.

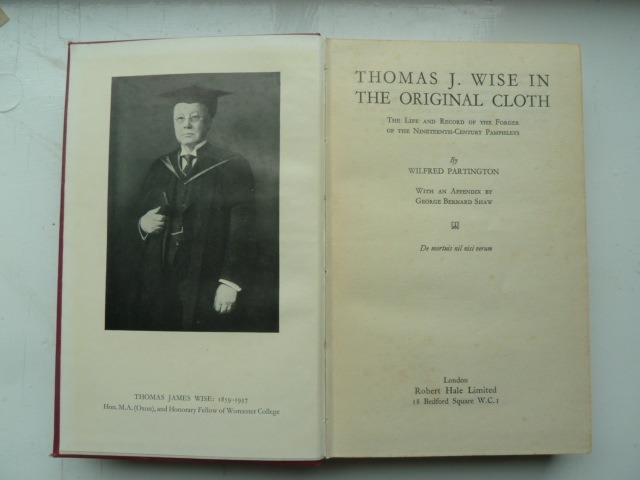

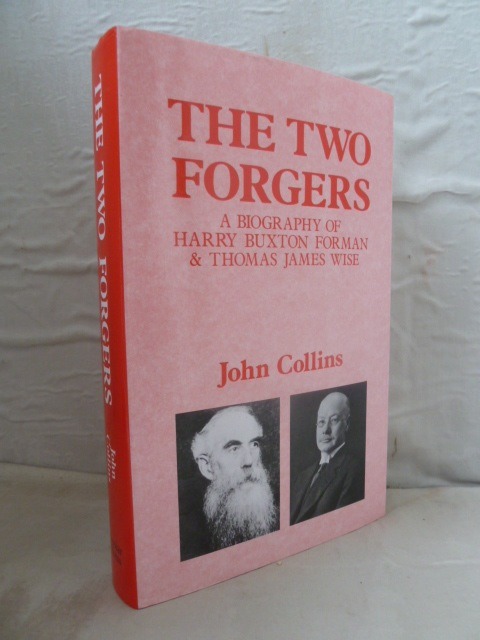

There are two excellent biographies of Wise.

In 1946, Wilfred Partington's study "Thomas J Wise in the Original Cloth" was published by Robert Hale and in 1992, Scolar Press published John Collins' "The Two Forgers", a dual biography of Wise and Forman. Both are highly readable accounts and leave you gasping at the sheer audacity of the forgers.

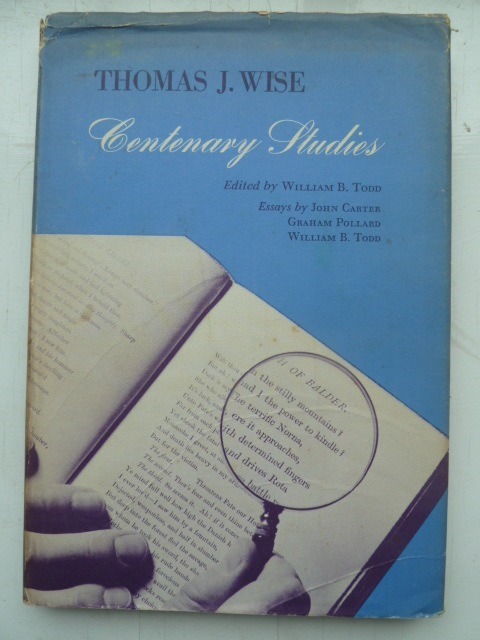

A comprehensive bibliography of all Wise's publications (both genuine and forged) is provided by William B Todd in his "Thomas J Wise Centenary Studies", published by the University of Texas in 1959.

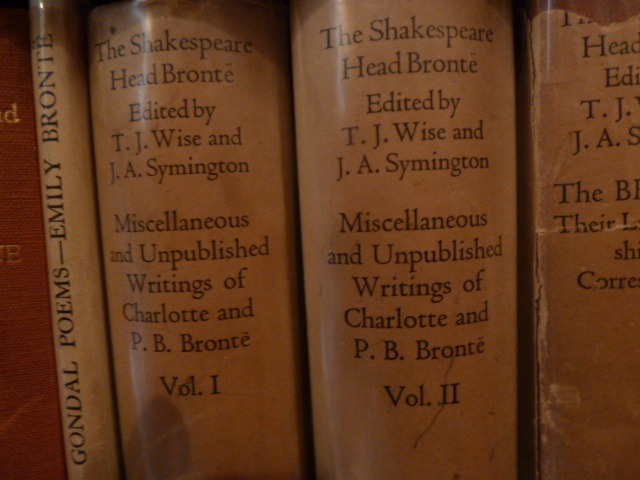

And, of course, forgery and theft aside, Wise was a great bibliographer and editor. With J A Symington he produced the Shakespeare Head Bronte in 19 volumes.

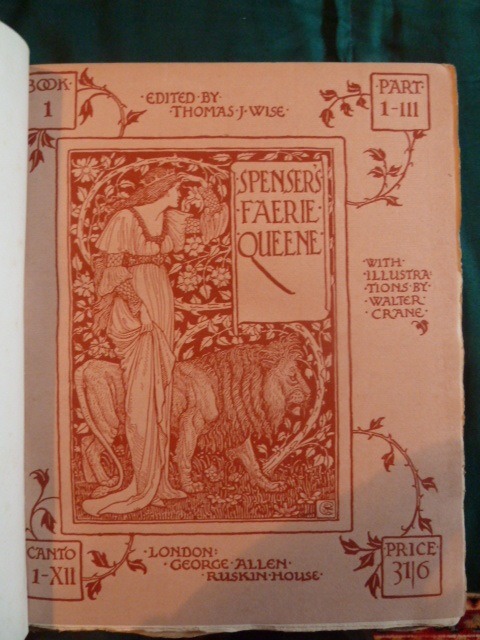

He produced bibliographies of Borrow, the Brontes, Browning, Byron, Conrad, Dryden, Keats, Landor, Pope, Ruskin, Stevenson, Swinburne, Tennyson and Wordsworth and a host of other publications, many beautifully produced volumes in small numbers, such as obsure letters of Ruskin or the Bronte Juvenilia (the originals of which he ruthlessly pillaged and distributed to friends invoking the eternal anger of Bronte scholars).

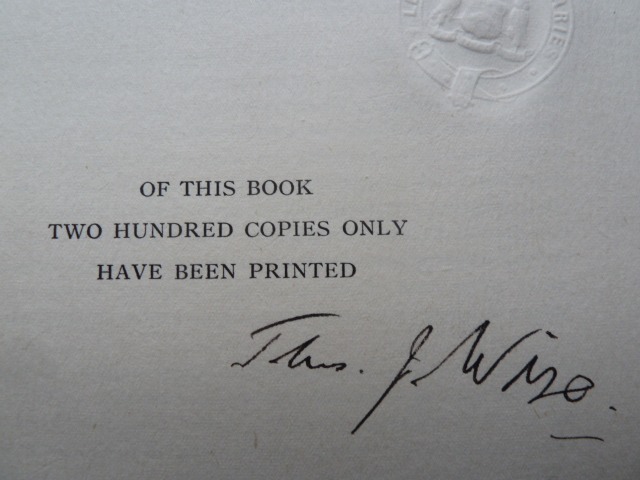

We found, to our surprise after purchasing our own set of the Ashley Library Catalogue, that it bore the ink signature of the great forger in Volume IX.

But, as with all things Wise, we must consider whether that signature is really his or just one more illusion left by this master of literary deception.

The Ashley Library was named after the suburban London road in Highgate where Wise lived when he commenced his collection.

The photograph above is a photograph of the road taken by my father-in-law Norman Webster accompanied by my future wife (then aged 10) in 1960. (It was from my father-in-law that I first acquired knowledge of the amazing story of Thomas J Wise.)

But it was at Wise's next house in Heath Drive, Hampstead (shown below) that the collection reached its glorious zenith.

Strange to think that in these typically suburban environs, one of the greatest private collections of English Literature was assembled and one of the most daring of literary crimes was planned. And even stranger to think that in his own library catalogue Wise (ever the most scrupulous of bibliographers) listed the very book that provided the evidence of these crimes.

Google Street View shows the house on Heath Drive to be remarkably unchanged since my father-in-law's photograph was taken. Perhaps, in the still hours of the night the floor boards softly creak beneath the phantom footsteps of its former owner in forlorn search for his lost library.

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPad