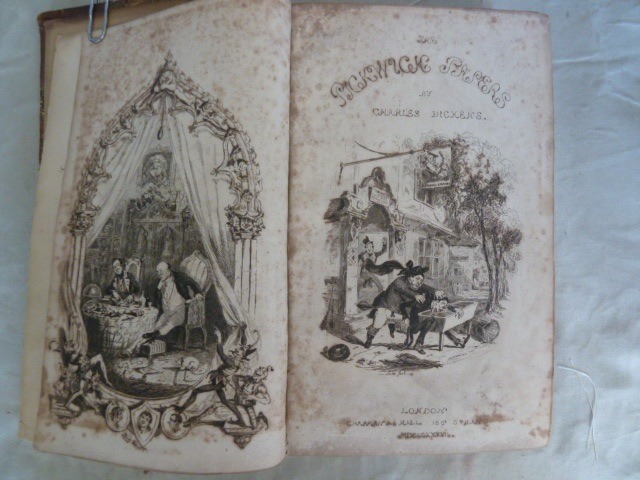

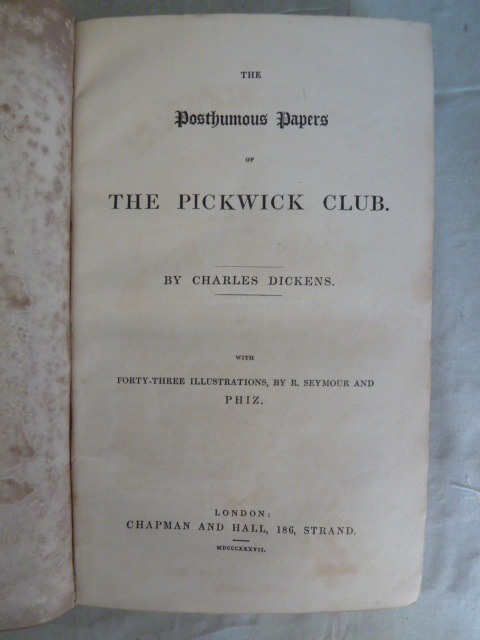

When I was young I did not enjoy reading Dickens. Maybe, this was due to early exposure to "Pickwick Papers" in English literature classes. I did not find the book amusing (despite being told I should by a teacher who thought every page was hilarious).

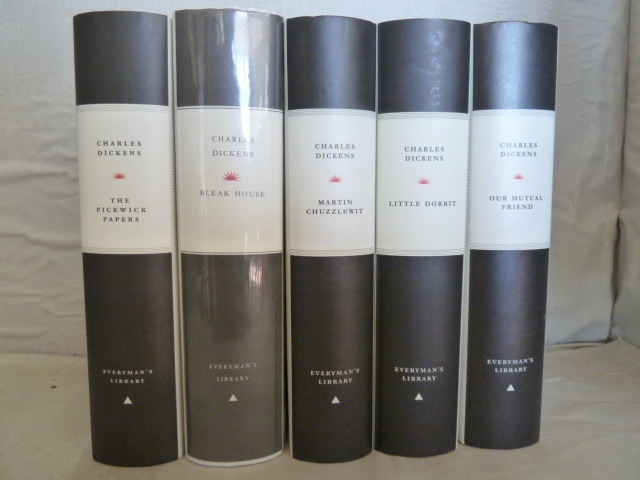

I still have an aversion to Dicken's early 'picaresque' books and have never returned to Pickwick, nor been tempted to try "Nicholas Nickleby".

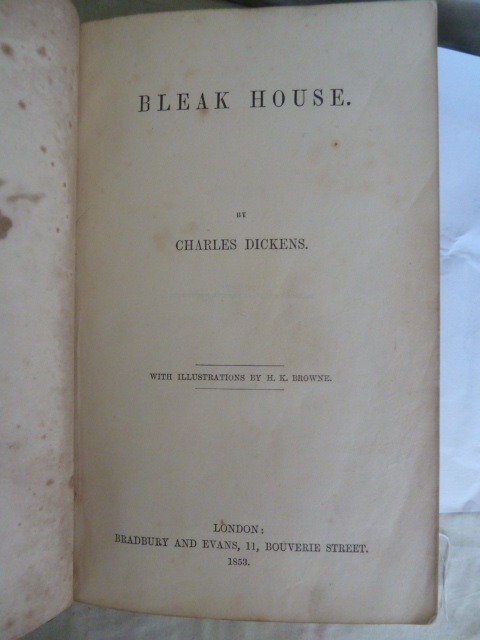

However, about 5 years ago I decided to read "Bleak House" and that changed everything. From its famous opening lines describing the fog hanging over London (a metaphor for the impenetrability of the legal system) to its dramatic climax when the case of Jarndyce v Jarndyce is finally resolved (to no-one's benefit but the lawyers), I found the book totally riveting. With its cast of wonderful characters, including Lady Dedlock (who I always picture as Gillian Anderson following the BBC TV series), the wards in chancery and the sinister lawyer Tulkinghorn it is perhaps Dickens' greatest work.

Since then I have picked off Dickens' later (sometimes called 'social condition) novels one by one.

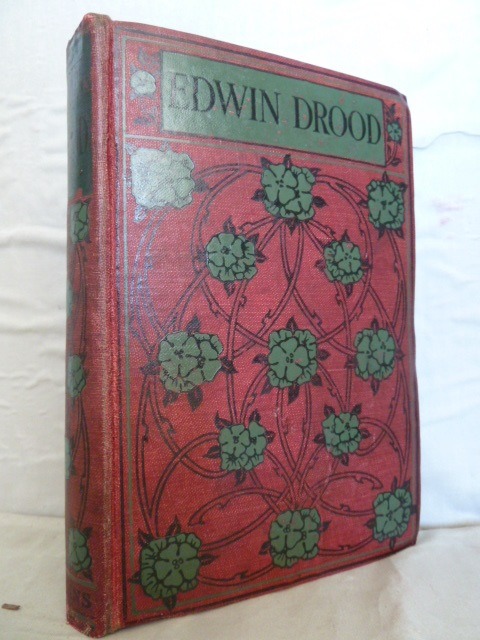

First, "The Mystery of Edwin Drood", with its brooding atmosphere and evil choirmaster John Jasper. Like all of Dickens' major work, this book was issued in parts and its author died with the novel incomplete, making it a perfect vehicle for literary speculation as to what happened to Edwin, who had mysteriously disappeared. This book is set in a cathedral city, based on Rochester, the city near which Dickens lived as a child.

Next "Our Mutual Friend". This is a long complex novel, which begins with the finding of a body in the Thames by one of the book's heroines, Lizzie Hexham and her boatman father. From this incident much of the plot derives and the story is essentially a murder mystery, with plenty of twists and turns until the good are rewarded and the evil punished.

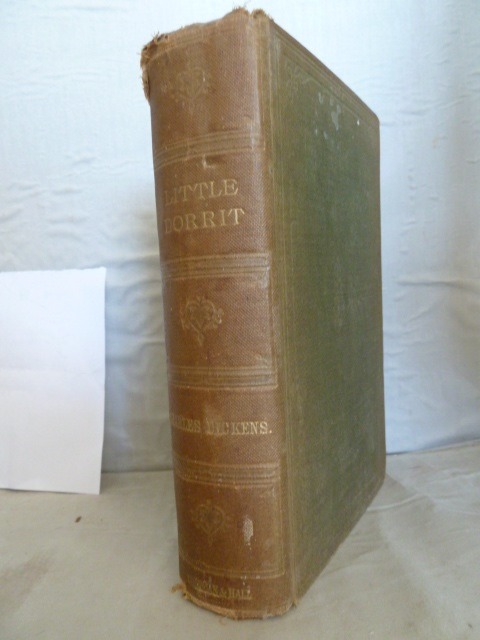

"Little Dorrit" was the next one I read. Here we are presented with the contrasting worlds of the Marshalsea prison in East London, where Amy Dorrit's father is imprisoned for debt and in which she was born and has lived all her life so far, and the world of high society inhabited by the crooked financier Merdle and his sycophantic friends. Amy Dorrit is possibly too good to be true as, following her father inheriting a fortune and taking her and others of his family and friends on the Great European Tour, she yearns for her simple life in the prison. She then sacrifices her own fortune to spare her husband's feelings (his supposed mother having wickedly kept it from her till the end of the novel) and lives happily ever after.

I have just completed "Dombey and Son" and have spent three weeks totally engrossed in the life of Florence Dombey as she keeps faith with her truly awful father, particularly following his financial and moral ruin and gets her reward as in his old age he dotes on her own children, giving the baby Florence the love he denied his own daughter until the closing chapters of the novel.

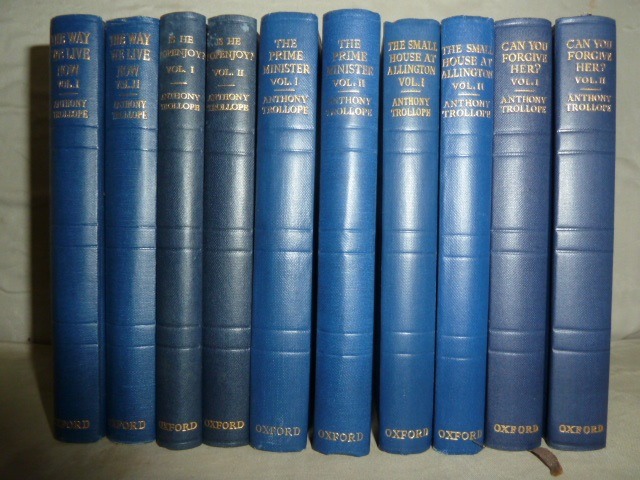

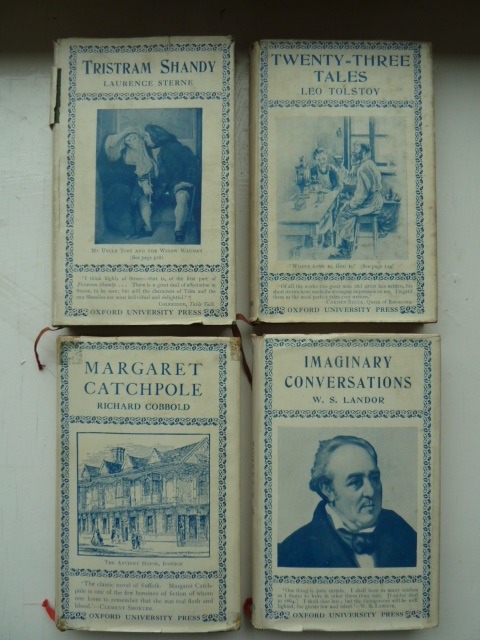

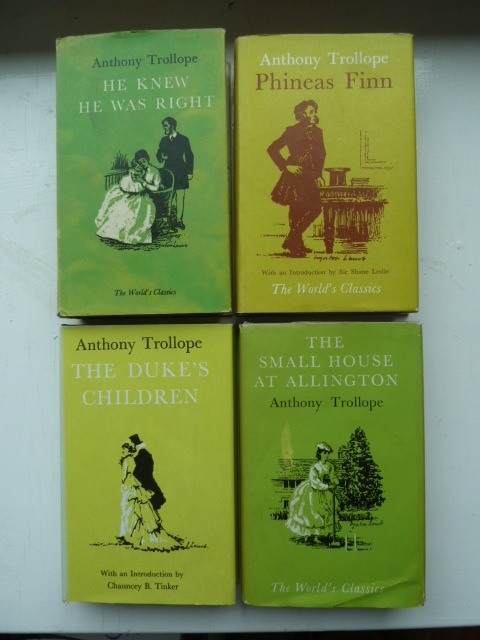

The astonishing thing about these novels is that they were each issued in some 18 monthly instalments and once a part was printed and bought by up to 40,000 readers, Dickens had to live with what he had written and future parts had to be consistent with what had gone before. This was standard practice for his contemporaries such as Trollope, Wilkie Collins and Thackeray, but it is a very different way of writing a novel to that of today when a complete novel is delivered to the publisher and makes far greater demands on the author. That the novels are, to a large extent, fully finished works of great skill and internal consistency is a tribute to how well Dickens managed his plots and characters, while maintaining his wife and children (10 in all), editing magazines, acting in theatrical productions and giving lectures and public readings. He also walked twelve miles a day in the afternoons.

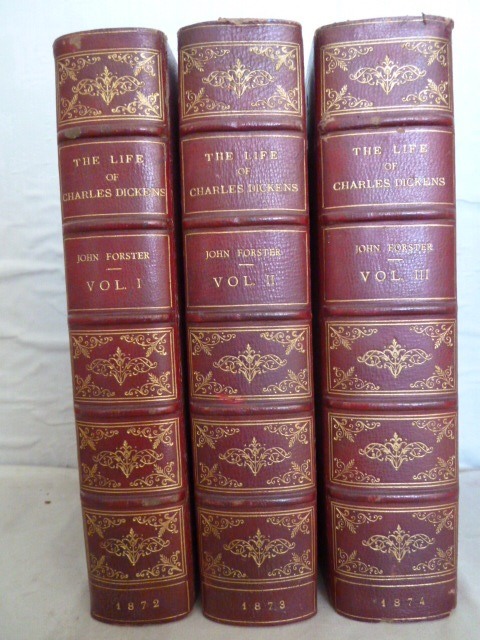

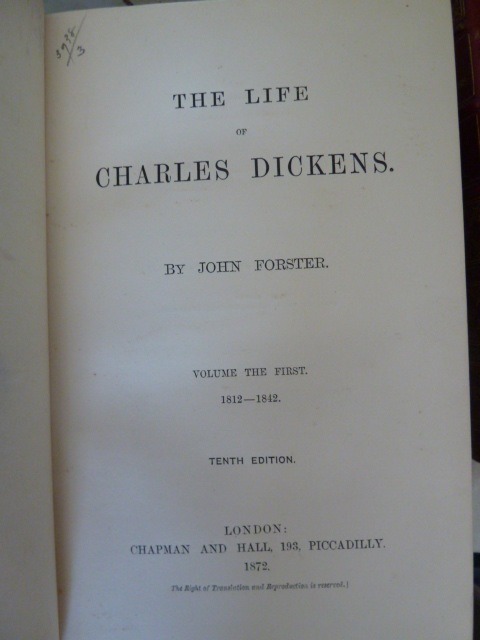

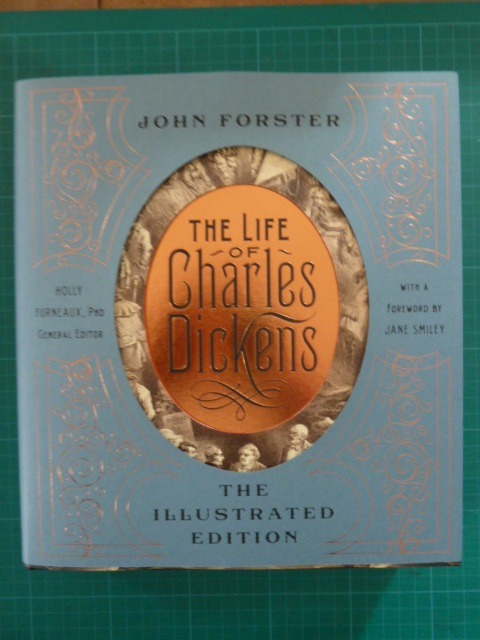

It being the year marking 200 years since Dickens was born, I also decided to read a biography. The classic biography was written by John Forster, a close friend and companion of Dickens, who was commissioned to write it when Dickens was still relatively young.

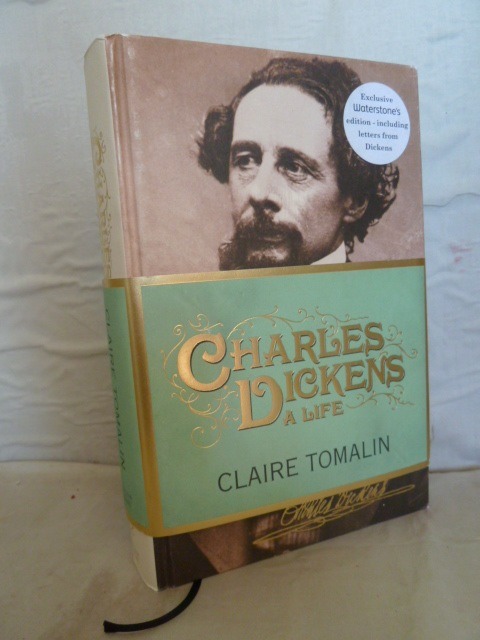

I have a copy of Forster's life in three volumes, but decided to read the recent biography by Claire Tomalin. This, like all lives of Dickens, owes much to Forster but is itself a very good account of Dickens' life and work.

Tomalin shows how his experiences as a child (when his parents callously sent him to work in a 'blacking' factory on the bank of the Thames just off the Strand became reflected in his books (via Oliver Twist and David Copperfield in particular). There is also a new abridged edition of Forster's biography recently published and beautifully illustrated.

Dickens left his wife Catherine after nearly twenty years of married life and plunged into an even more energetic way of life, with lecture tours in Britain and a second trip to the United States. At this time he was very close to the actress Ellen Ternan, but their relationship is unclear. As a human being Dickens had his faults and could be needlessly cruel, as when he portayed his friend Leigh Hunt as the sponger Skimpole in "Bleak House" and even parodied Forster in the character of that defender of middle class values Podsnap in "Our Mutual Friend". His readers, however, loved him and it was only fitting that on his death in 1870, at the relatively young age of 58, he should be interred in Westminster Abbey.

I still have several major works to read - "The Old Curiosity Shop" (where I am assured by Oscar Wilde I will need a heart of stone to avoid laughing at the death of Little Nell) and "David Copperfield" (Dickens' own favourite of his novels) to name but two.

So why read Dickens? Because, for all his faults, for all his unbelievable plots, for all his meanderings, his novels are still as fresh, relevant and true as when they were written. He was aware of his talents and drove hard bargains with his publishers, but he knew he was worth it and his books have sold in their millions all over the world.

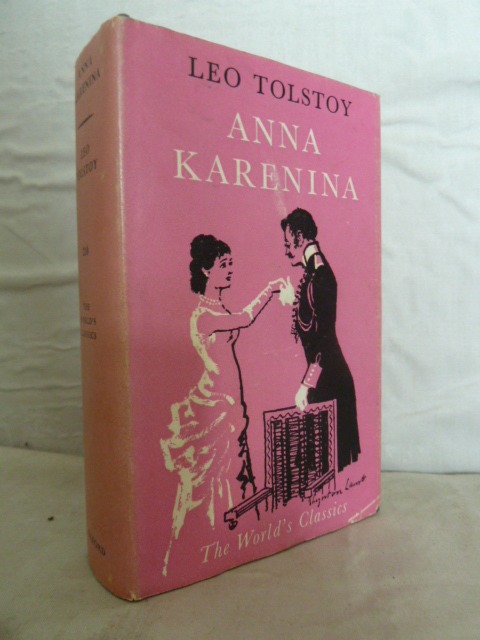

I am particularly attracted to the modern Everyman editions of Dicken's works, which are well edited with long introductions and bibliographies and contain original illustrations by artists such as H K Browne. However, I have read "Our Mutual Friend" "Little Dorrit" and "Dombey and Son" on a KOBO e-reader. I hope the author would have approved.

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPa,